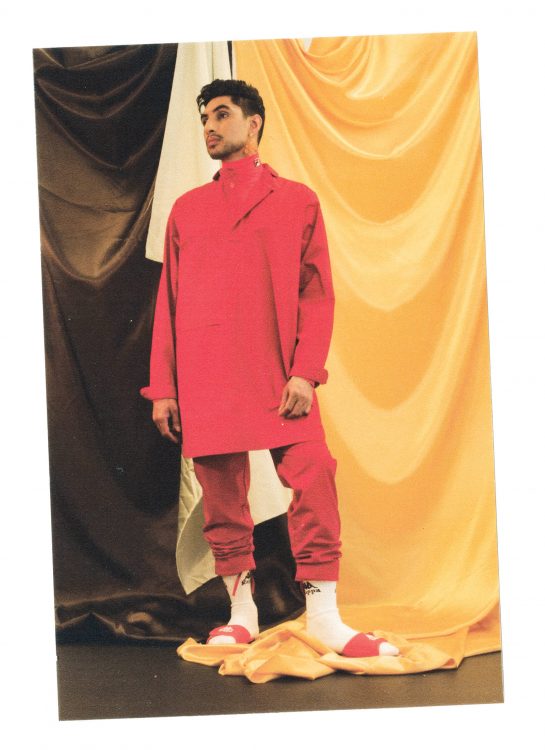

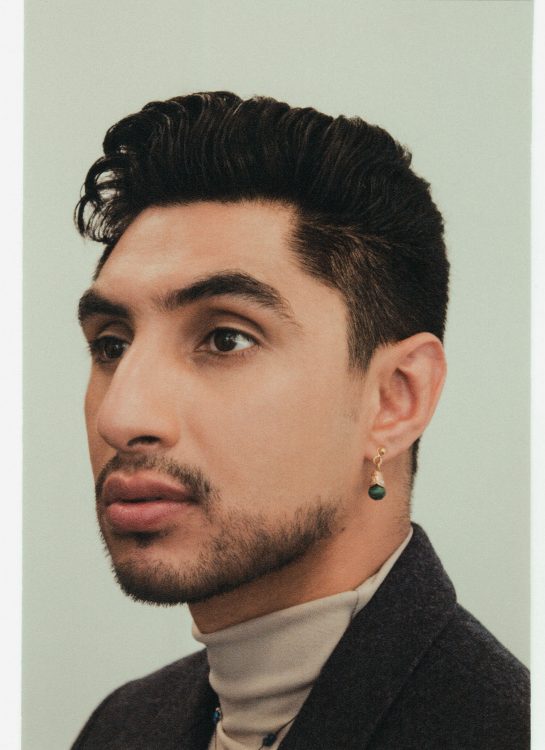

- Words Russell Dean Stone

- Photography Yis Kid

- Fashion Neesha Champaneria

Introducing the Lion King.

“There’s a massive friction between my cultural identity and my sexuality,” begins British-Pakistani dream-pop artist – Leo Kalyan. Since emerging in 2014, Kalyan and his oceanic smooth-grooves have hit number one on Spotify’s Global Viral Chart, he’s been on a headline tour of China (where his music has found an unexpectedly devoted fanbase) and his songs have gained celebrity fans as diverse as Rupaul, Diplo, Maxwell and Tegan & Sara – and he’s done it all totally independently.

From the age of 10 until he was 17, Kalyan did his growing up between the contrasting worlds of South London and a city on the border between India and Pakistan, called Lahore. Kalyan always felt that South London was home and that going to Pakistan was like visiting a foreign place. Kalyan says it’s indicative of our particular moment in history where people from diasporic communities, like himself, are re-examining what it means to be from ‘somewhere else’.

“People of colour these days often talk about being asked where you’re ‘really from’, but I wasn’t just asked where I was really from in London, I was asked where I was from back in the place where I was supposed to be from, too,” Kalyan exclaims. “I’d be the foreign kid in Lahore and in London.”

Kalyan’s cultural background means he’s not only bilingual linguistically but musically too. Fluently speaking and thinking in Hindi, Urdu and English, his training in Indian classical music, as well as obsession with Bollywood and Western pop, mean he’s sonically bilingual too. “My mum was listening to Madonna and my dad was listening to the Eagles – but I was also fed endless Bollywood songs: artists like Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosle, and Pakistani folk musicians like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Reshma,” says Kalyan. “It was a really eclectic mix of sounds, and that’s probably why my music has ended up sounding like it does.”

Once you know this, Kalyan’s music starts to make proper sense. His artistic mission is to make music that reflects all of his influences and accurately represents him as a truly multicultural human being. It’s all about deconstructing the conflicting intersectionality of being, what he describes as, “someone who is gay and brown and from a Muslim background.”

“I’ve certainly had my experiences of trying to make music that perhaps sounded more novelty than authentic, where I was experimenting with sampling to produce music that sounded more recognisably Indian or South-Asian.” Kalyan says, explaining that finding his voice was no easy process.

In fact, Kalyan’s journey from anonymous Soundcloud entity to the articulate, open and outspoken artist you’ll find today, hasn’t been straightforward at all. Back when he dropped his first track – a mashup cover of Duke Dumont and Jessie Ware – he wasn’t ready to put his full self out into the world publicly. Instead, Kalyan “felt safer hiding behind artwork” by not showing his face or discussing his identity, but looking back he can see how much has changed. “I hadn’t yet found a way to balance my identity as a young gay man from London with my identity as someone that comes from a Muslim background, whose family is Pakistani and Indian,” explains Kalyan. Much of his anxiety at the time was rooted in fear – the fear of being found out, the fear of being rejected by his family, the fear of being criticised and the fear of being judged.

The way Kalyan overcame these fears was by facing them head on: “I hit a point where I realised that not being my full self was holding me back in my personal life. I had commitment issues in all my relationships because at the back of my mind, I believed that they couldn’t last, or feel legitimate. When I looked at my work, I wasn’t writing honest music that fully represented me, there was a kind of hollowness there. Looking back, I know how much everything’s changed since I came out to my dad and put my identity out there, albeit slowly… in small steps.”

Constantly policing himself was deeply suffocating for Kalyan because over time it “fucks you up” to find yourself suppressing different parts of yourself depending on who you’re with. Kalyan credits his friends for giving him the clarity, confidence and support he needed to embrace himself fully: “One of my best friends is MNEK and he is a young, gay Nigerian man trying to balance his sexuality and culture in a very similar way to me. That’s one of the reasons we’re best friends. Talking to him, somehow really helped me untangle things in my head.”

"fucked up" by Leo Kalyan

This personal untangling led to the release of Kalyan’s 2016 EP, Outside In. The record was a coming-out moment to his fans, and attempted to unpack his feeling of being “on the outside of the outside of the outside” – as someone who falls into multiple minorities — gay, South-Asian and from a Muslim background – and as somebody who routinely has some part of their identity attacked or demonised by the media and society on a daily basis.

“Islamophobia has absolutely been normalised. And nobody gives a shit. For many parts of society it’s perfectly okay to be homophobic, especially behind closed doors. Racism, xenophobia and the far-right are on the rise all over the world. But fuck it. I’m going to be myself because I’ve got one life to live and one chance to be me.”

Despite the fact that on paper Kalyan ticks all the boxes that would typically lead to someone being signed to a record label, he remains unsigned. In early days, enthusiastic record labels would rave about his music, but upon discovering his identity, their interest would quietly evaporate – with Kalyan even being told by a label friend that they’d overheard someone commenting that “it would be so much easier if he was white”. To him, it’s absolutely no surprise that his contemporaries have been snapped up and invested in, while he’s left on the bench.

“Brown people are still not getting signed. Record labels don’t invest in South-Asian talent, so in turn, brown kids don’t pursue music careers. It’s really that simple. Think for a moment how few South-Asian people there are in the music industry, apart from M.I.A… Mainstream platforms like BBC Radio 1 are partly to blame because they don’t support South-Asian artists. Imagine if they didn’t play any black artists on Radio 1. Imagine if they said ‘all black artists need to go to Radio 1Xtra or BBC Caribbean’. That’s sort of what happens with brown musicians – they’re ghettoised to the BBC Asian network, and even if they rise to the top there, they aren’t allowed to cross over to mainstream radio. It’s shocking.”

It’s a bold statement, but Kalyan says it’s worth the risk to speak out on these issues, and besides, he’s had to side step through his whole career anyway. He talks about the importance of representation, and the responsibility that record labels and radio stations have in helping to facilitate this. “Young, brown people desperately need positive role models. We’re being alienated from society,” Kalyan says, citing it as an example of how South-Asian people are prevented from integrating into society and wider culture in Britain. “Music is powerful. Seeing yourself reflected within popular culture is powerful. I’m not the only one saying this… Riz Ahmed, Meera Syal, they’ve all gone on record to say these things. But no one cares. It reminds me of the line from George Orwell’s Animal Farm, ‘all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others’.”

Kalyan cites the Spice Girls as huge influences (“Seeing powerful and rebellious women is inspiring – they were out with their friends, wearing and doing things they weren’t supposed to be doing”) as well as George Michael (“He was unapologetic about who he was, after spending half his career pretending to be straight he was like ‘right, this is who I am – and I’m gonna take it outside’”). He says he’d rather be Rihanna than Beyoncé because Rhi-Rhi is also unapologetically herself: “Her zero-fucks-given attitude is what makes her so empowering. She’s totally in control of herself and does not care what anybody thinks – in many ways, isn’t that freedom?”

Personal emancipation for Kalyan has come as a result of turning other people’s perceived negatives about him into superpowers. Someone who really taught him that was RuPaul, who advocates turning your ‘trash into treasure’. “Watching Drag Race, I thought ‘if these people can put their full selves out here for all the world to see, to this extreme… then what I’m doing is just a baby step in comparison. Drag queens have such guts, such courage, such determination and such real talent as well!”

“Everything that I thought was trash about myself, everything that I thought people would reject – that is part of what makes me unique. It’s about bringing all those things together to present myself as a complete human being,” Kalyan continues. We discuss the idea of being yourself as a political act, especially in the context of how invisible queer South-Asian people are, especially within their own community — seeing as it’s still illegal to be gay in Pakistan, and India has only just overturned it’s laws around sexuality.

“Section 377 was a British law from colonial times, and it’s taken this long to overturn it” asserts Kalyan. “Now, it’s genuinely a political act to be a queer person in India – and we don’t yet know how society will react to us coming out of the closet… But queer people have existed within the South-Asian and Islamic world for time immemorial, we just need to have courage to emerge from the shadows. We don’t need to be invisible anymore. It’s all about listening to some Rihanna and feeling yourself and being that bad bitch who does whatever the fuck she wants” he says, laughingly. “But really, I don’t think that demanding the freedom to simply exist is asking for much.”

Next up for Kalyan is a trilogy of mini-albums featuring tracks that explore cultural sociopolitical issues, as well as straight-up pop songs about heartbreak and boys. Kalyan says the new music brings together all the different strands of himself, “It’s like I had all these little horcruxes hidden away in different places and I’m bringing all the horcruxes together to bring my full self to the table,” Kalyan laughs. “It’s about being lost, going on a journey to find yourself and coming out on the outside – literally coming-out on the other side!”

Kalyan says he finds that far too many queer people of colour don’t truly believe they’ll ever be happy, “I never, ever, ever, ever thought that I’d be able to introduce a partner to my parents. I never believed that would happen for me. It still shocks me that my dad, a Muslim man, actually found a way to reconcile who I am with what his beliefs are. It’s just proof that people don’t always behave in ways that you’d expect. The amount of love and messages of support I get from queer people of colour all over the world, just seeing that stuff has changed my life.”

“It takes real strength to be a queer person. You go through so much shit – so much discrimination, abuse and rejection – whether you’re black, white or brown. Find that strength, find that support from your community – and find a way to be your true self… because you’ve only got one life. There’s no point wasting it trying to be someone else.”