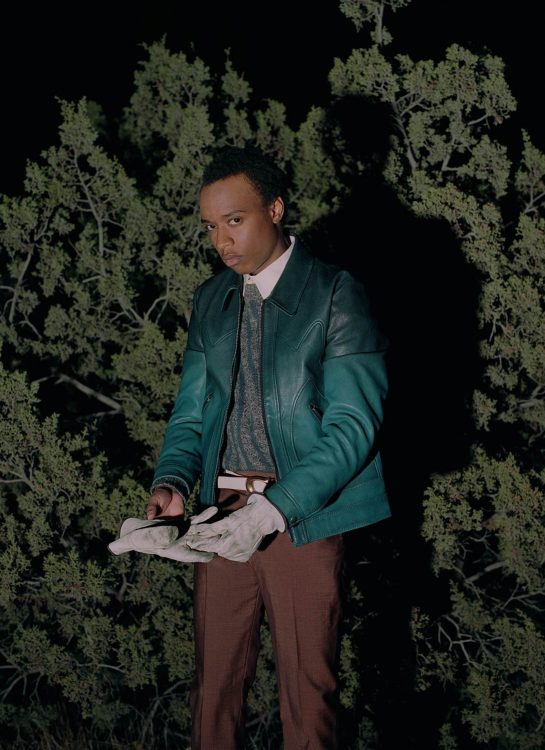

- Rejjie wears Coach

- Words Notion Staff

- Photography Damien Maloney

- Fashion Ashley Guerzon

- Words Tasbeeh Herwees

- Grooming Bailee Wolfson

- Fashion Assistant Jillian Newman

Ireland's premium export talks fucking with Italians, epiphanies and being a different breed of hip hop artist.

“I’ll answer anything”, declares the artist known as Rejjie Snow from the rooftop of a Koreatown hotel on a warm day in Los Angeles, “conversation is where I learn the most things”. The Irish rapper—born Alex Anyaebunam—was a resident in this neighborhood, living in a cockroach-infested apartment for a year back when he was 19. At that time he was dating a girl and things were crazy. When asked to explain, he talks about the night he came home to find all of his belongings splayed outside in the street. Snow had never met someone so passionate about anything. He refuses to elaborate further but describes them both as “super immature”. “I didn’t know how to communicate properly my feelings,” he offers as explanation.

If Snow’s debut album, Dear Annie, is anything to go by then, when it comes to expressing his feelings effectively, he’s come a long way. The sprawling 20-track LP is his first big project since signing onto 300 Entertainment in 2016—joining a roster that includes Young Thug, Shy Glizzy and Fetty Wap—and is the reason Snow is back in LA. The label released the hour-long album in three digestible parts, with two intermissions to help break it up. Taking obvious influence from N.E.R.D. and Tyler, The Creator, the 24-year-old Dubliner designed an atmospheric record that explores love and identity. His nonchalant vocals hover over dreamlike melodies and beats that borrow from eclectic influences including funk, American jazz and hip hop traditions.

Snow was born in 1993 to a Nigerian father and Irish-Jamaican mother in Dublin. He moved to London at 16, where his primary occupations included graffiti and football (which would relocate him to Florida on a scholarship). At 17, during his second year of high school, what Snow vaguely describes as “mad epiphanies” were a real catalyst that led him to realise that music was his calling. There was a genetic relationship between graffiti and music, and his involvement in one opened the door for opportunities in the other. “Everything I did that year changed my life a little bit,” Snow affirms, “I was a way different person back then but I fucked with myself back then. I coulda easily done something else. There was a lot of negativity in my life but whatever it was about that year, I just stuck with my guns.”

His experiences as an immigrant in London, as the son of immigrants in Dublin, and later as an immigrant and black man in America, inform his identity and status as an outsider. During his teenage years Snow spent hours each day surfing the internet, making connections online and lapping up cultural knowledge. “Where I’m from is such a negative place,” he says. “I had to remove myself from that negativity and work with the kind of skills I had at the time to put my music out there. The internet helped a lot.”

Snow’s internationalism pervades Dear Annie, seeding it with references to Jerusalem and French lyrics. There were complaints from some quarters that the album wasn’t quite Irish enough, that it more frequently calls back to American music traditions than Irish rap and hip hop genres.

- Gloves, shirt and jumper Stylist's Own

- Jacket and Trouseres Coach 1941

- Belt Coach Signature

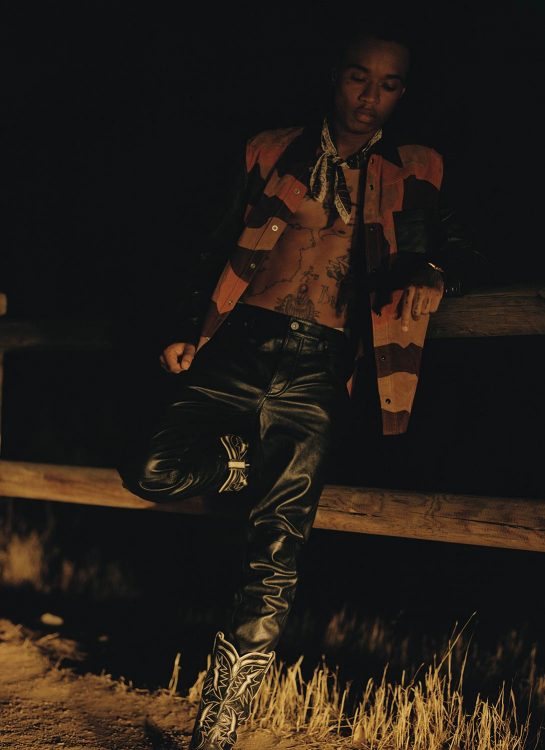

- Shirt and Belt Boots tar

- Trousers Coach 1941

“That’s funny to me because I grew up in that place, which at times felt like a real jungle, you know?” Snow says. “What I choose to do and say in my music has always reflected what’s around me, I don’t like dwelling on the past… I left Ireland super young and I’ve been dotting all around ever since and that’s where I feel my music exists. I guess you’d have to live there to fully know the connotations, slang—all that you can find in my music. The idea people have of what being Irish is, I’m always trying to bend because I’m an Irishman true and true but right now I’m focused on making stuff for the world and all its inhabitants.”

When discussing his influences Snow is hesitant to name contemporary artists—though he listens to a lot of Stevie Wonder and thinks Solange is pure excellence—but becomes animated when talking about the films he loves; describing how he constructs albums like films, piecing together throughline narratives for each project, with Italian crime dramas providing key influence for Dear Annie.

“I fuck with Italians. especially in America,” he says. “That’s the inspo, swag.” A Bronx Tale is his favorite, a 1993 Robert De Niro flick about the tensions between Italian and black communities in 1960s New York. The film’s smoke-filled rooms, the tortured romance at the heart of the film and the racial and economic politics that structure the film’s central relationship, all infect Dear Annie with dark energy.

“I first seen it when I was mad young and I remember it resonating with me so crazy,” he says. “One of these kids from the italian neighborhood falls in love with a black chick and that causes all this commotion in the community because he’s dating outside of his race. It’s about family values, religions. And there’s the O.G. who’s obviously looking out for all the kids and telling them how to navigate through shit.”

There were hints of his obsession with Italian-American culture sprinkled throughout his early music. After moving to London at 16, Snow briefly headed to the USA to attended the Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia to study film (Snow wants to make films one day, or at least soundtrack them) while releasing music under the moniker Lecs Luther. “Dia Dhuit”, titled with a Gaelic greeting, came out in August 2011—“Coughing up that crack I call it a John Gotti / Inciting a riot and massacre, fuck a slave ship,” he raps on the track, referencing the Italian-American mobster from the 80s. He even shouts out pasta!

Snow got some of his hip hop education via Playstation games—like Grand Theft Auto and Tony Hawk and their 2Pac, Public Enemy, and Cypress Hill featuring soundtracks—learning how to make beats through YouTube. When he released “Dia Dhuit” as Lecs Luther, indie hip hop blogs geeked out, impressed by the acuity of his lyrics and the ease of his delivery. By the time he finished his first EP, Rejovich, in 2016, he’d racked up enough cultural clout with music heads that the record very briefly topped releases from Kanye West and J. Cole on the iTunes chart.

“I don’t really want to have an opinion on nothing,” Rejjie says, in a surprising admission. By all accounts, the lyrics on Rejovich challenge this claim. For example, opening track “Loveleen”, is full of political fire: “The kids ran riots / While the black kid rapped / And a story of a city and the hatred for the piggies fuels fire in the bones”, he intones on the song.

“I’m a lowkey cat unless I’m deep in a conversation”, he tells me now. His relationship to the Internet has changed. He’s not online for more than an hour these days, and it’s time usually spent on YouTube. If anything, he’ll check Twitter because it “gets really wild”. I tell him I think Twitter broke my brain, that the constant stream of opinions overwhelms me and short circuits my thought process. “So many opinions,” he agrees. “A lot of mental health problems on those apps.” He doesn’t tweet much, though. He doesn’t feel pressure to constantly check his Instagram, or reach out to people. “I just want people to know that I don’t give a fuck. I’m just trying to do me.”

When I go to check his Twitter, I discover this opinion: “james corden is the most annoying cunt ever fuckk.” And then, a follow-up, not even an hour later: “okay that was kinda mean we all have a job to fulfill & kids to provide for. Sorry for projecting that negativity into the world when there’s already enough but he’s still annoying.”

It strikes me that Rejjie Snow has lots of opinions, probably, but like many young artists, he’s struggling to settle into his role as a public figure, as a person that people are watching, listening and looking up to. “The last two years I just been tripping out on the fact that people, as far as I’m concerned, care about the shit that I’m doing,” he says. “Especially younger people. That’s really dope to me. You know when you’re young and got role models, it means alot more than you think. So, for me it’s like now that I got that, I just really want to keep pushing what I’m trying to do and get my message across, whatever I’m trying to say.“

- Shirt and Belt Boot Star

- Trousers Coach 1941

When pushed on what that message is, Snow confesses he never really wanted to have one.

“For me, making stuff only serves one purpose and that’s feeling,” he says. “As much as I can talk about things I often obsess over how it sounds and the sonics—which kinda plays a more important role when executing the product. But if I can inspire that’s all I hope for ‘cause inspiration is priceless and I’m so down for that.”

Maybe he won’t admit it, but there must be something terrifying about being watched and making mistakes in public, by an audience of thousands at 23 years old. Every artist reacts to this kind of pressure differently, but it looks like Rejjie is still figuring out how he wants to do it. “I care less I think. Just because I haven’t found too much on the Internet that’s good for me,” Snow says. “Until I do, I’ll be back on there. I feel like I have a platform now.”

“I find it hard to be a creative person here,” Snows says gesture out at Los Angeles. “I feel kind of insecure around everything. There’s so much madness going on.” Snow doesn’t drive, so the unwalkable streets make the city difficult to penetrate, but he does approve of the legal marijuana situation in LA, likening it to a “candy store”. “Where I’m from they grow it as Chinese restaurants, all through the chinese mafia,” Snow says. “So it’s like a human rights issue. If you smoke weed where I’m from, you’re supporting that shit.”

He doesn’t like being on tour because it messes up his routine—gym three times a week, football, walking the dog, hanging with his friends, drawing sometimes. But when he’s touring, every minute of every day is structured around the one hour of time he will spend on stage at that city. When Snow takes the stage the next day at a packed El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles, he’s wearing kelly green track pants and a black and white track jacket. His only pre-show ritual is the burning of incense. “Any kind. All types. That smell—whatever it is—calms me,” he says. He grew up in a semi-religious household but doesn’t practice himself, so pre-show prayers or supplications are out of the question.

“I don’t really live by any kind of commandments,” he says. “When shit be happening, every question I have with myself, I don’t really ask god about. I just ask my pops. He tells me what’s up.”

At his performance he shuffles across the stage nonchalantly, singing his lyrics as though serenading a private audience. He sings like some people sip on a glass of expensive whiskey: slow and leisurely. “This ain’t a hip hop show, this is an experience,” he shouts out.

Rejjie wants to be a different kind of hip hop artist, to be, in his words, “an alternative to what’s out there”. “I think I’m ready to put the gears in motion,” he says, “Take things to a different level… I want to be remembered as someone that went against the grain.”

“I try to stress that I’m a human before anything thing that I do,” Snow says. “All the mistakes I make are because of being human. I try not to be too apologetic because I think that’s part of why I want people to like about me. I’m myself. Not too caught up in everything.”

- Top Stylist's Own

- Shirt and Belt Boot Star

- Trousers Coach 1941

- Jacket Coach Signature

- Shoes Coach

- Jacket and Trousers Coach 1941

- Shoes Boot Star