- Words Notion Staff

- Interview Holly-Marie Cato

- Words and Editing Leanne Petersen

- Photography Vicky Grout

- Styling Marc Biakath

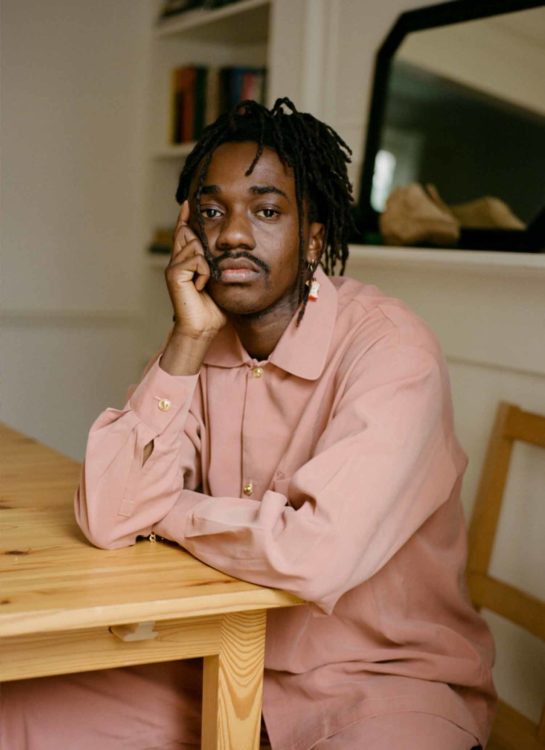

'Worldwide funk' artist and rapper, Ric Wilson, speaks with photographer Holly-Marie Cato about the time he spent in the UK, from the new slang he picked up (and got tattooed on him) to the friends he made and much more.

I’ve been a Ric Wilson fan long before we met in London earlier this year. My favourite song by the Chicago native is “Sinner”, a fun alternative hip-hop sound featuring Kweku Collins, Nick Kosma, Rane Raps and Hirsch. I loved Ric’s ability to blend funky, fusion dance sounds with hip-hop and rap about social political issues on seemingly dance-oriented tracks. When we first connected back in April on Instagram through a mutual friend, Ric told me he would be travelling to London in a couple of weeks. So I suggested we meet in person at one of my favourite outdoor spaces: Victoria Park in East London. We spent the afternoon walking, drinking coffee and taking photos. What immediately struck me about Ric in those first conversations is his awareness of the differences between White and Black British culture. He also sees the nuances amongst Black identities across Britain and how they differ from his own identity as an African American, despite how, for so long, all “cool” depictions of Blackness in the media were most often through an American-centric lens.

After spending four months visiting the U.K., Ric returned to Chicago this summer to begin preparing for his first live performances since the pandemic started. We re-connected a few weeks ago, this time sadly not in person, but on a call, to continue our conversation.

- Shirt La Boutique

- Shirt La boutique

Holly-Marie Cato: Hey, you just woke up, what’s the time there? 9 am?

Ric Wilson: Yeah, it’s nine o’clock, I had a seven-hour rehearsal with the band yesterday which was crazy. We didn’t rehearse all of January, and we didn’t rehearse any of 2020, so we had to learn a whole bunch of new songs and I didn’t realise how much that took out of me, until now. I’m just adjusting, you know what I mean? I was really in an English world. Even with slang and the way I’m talking, folks be looking at me here like bro, “Why you talk like that?” I guess l am talking a little weird now.

What’s some English slang you picked up?

I can’t stop saying, “To be fair”.

Ha-ha! That is definitely English — “to be fair” — or we just apologise for nothing, like, “Sorry but…”

Oh, no, see, I didn’t stay [in England] long enough to become polite. I’m still a little rude. But like, ‘To be fair’, or ‘Fair play’…I actually I got ‘Fair dues’ tattooed on me!

No, you did not… Why did you choose ‘Fair dues’?

I was around a lot of Geordies the majority of the trip, so I be saying things like ‘Oh that’s a belter’ or ‘too right’ or I’ll call something ‘a good shout’. You know what I mean? Just like little things.

‘Fair dues’ is definitely something that an older generation would say, but you would say it almost sarcastically, I guess.

Yeah, exactly, so I would always say it sarcastically. The reason I got ‘Fair dues’ tattooed is because it reminds me of ‘Facts’, or ‘Oh, true’ you know what I mean? I feel like you got the same conations in the UK. So, people would say something like, I don’t know, like, yesterday England won, they scored three to one, I’d be like, damn, “Fair dues,” you know?

- Coat A A Spectrum

- Top Mr Albarella

- Jeans Collusion

- Shoes dr. martens

Yeah, well, you clearly understand the English lexicon.

And then also with ‘Fair dues’ I can say that all over England. Like when I went to Manchester or Newcastle or Surrey and I said ‘Fair dues’ people would just know what I mean. Versus like, I guess people saying ‘Peng’, but people [from Manchester] didn’t really use ‘Peng ‘like that. You know, I mean? …The people I was around they’d say ‘Lush’. ‘Oh that’s Lush’ or ‘that looks lush’.

I know you told me before but remind me, was this your first trip outside of America?

Oh yeah, this was my first trip to the UK but not travelling outside of America. My first time was when I was 19, I went to the UN that was a really intense ass trip. I went to the UN to present a shadow report to the United Nations, from there we spent the day in Paris, which was very interesting, It’s still a blur in my head. When I turned 21, I got hired by a University here in Chicago, to go study the Khmer Rouge and the effect that it had on Cambodia. So, I went to Cambodia to do that and came back and created a curriculum for the University of Illinois in Chicago. Cambodia was my first time outside of the bubble and I understood what being outside of the bubble could be. I feel like in Cambodia, your American privilege won’t protect you from certain things. So, I think that’s what I’m trying to say the European whiteness bubble-like your American privilege can like protect you from certain things, but like if I got into it with somebody from Cambodia, my American privilege probably wouldn’t protect me from that.

Okay, so why London, why now?

Well, it was October 2020, the height of the election. I went camping in Michigan, which I had never done before. I saw these white folks throwing their own Trump parade. So, I was just like Man, I gotta leave. I gotta get out. It was like there was just too much going on in the United States. It was like a pandemic, uprisings, election — it was just too much. I had a headache. So, I decided to leave. I was like, where can I go for a little bit next year and you know, just clear my head and get like a hard reset on how I view life right now. I had also never been in Chicago for so long as I’ve been traveling around the states so much in the past two or three years. I felt like a domesticated cat that used to be an outdoor cat and now I was a domesticated cat that had to be indoors. So, I was like, where can I go? Who’s letting me in, and I looked up flights for London. I didn’t know how fucking different it was, but I knew they spoke English there and I found a flight, and I was gone.

Okay so you were in the UK to escape Trump and the echo chamber that I guess everyone was in, in America.

Yeah, I was like, this is gonna be different but at least I’ll know what the hell people are saying. I don’t have to worry about trying to tighten up my Spanish or be worried about the fact that I don’t know French, you know. I’ll catch on to how they talk, and it will be easier for me to make friends. When I came to London, I only knew one person, well two people kind of, actually I knew three people. But one of them I only knew from Instagram, my friend Dami, who’s a Nigerian student that lives in London. Then I have my friend Fergus who doesn’t do music, he’s one of the lads from Newcastle and then I had Yellow Days. I knew Yellow Days through Instagram but never met. So, I came over kind of not really knowing anyone but then leaving London, I probably have like 40 new friends.

- Coat a a spectrum

That’s amazing. So, did you have any expectation that you were going to come and make music here?

I had expectations that I was gonna come and make my music by myself. I brought my mic, my whole little setup. The crazy thing is I didn’t even use it. I used it like one time when I was in Forest Hill for the first month and a little bit of May. But after that maybe once or twice, but as soon as I got here people were like, yo, pull up, come to a session with me. I knew you guys were locked down, but I didn’t know how intense your lockdown was until I got here. Because in America, I guess like America and England are like in the same bubble. But America is in its own little bubble and we really have no idea what the hell’s going on elsewhere. So, when I came here, I just learned so much about England that I did not know, especially with y’all lockdown. I had no idea about the six people rule because when I came, y’all was still in this lockdown hardcore. So, I made like a lot of new friends just doing sessions and then going to their house after sessions to do small gatherings with flatmates or friends you know, I mean before everything opened up. That’s how I met a lot of folks who knew a lot of different musicians like I think they went from like one person who was doing a session like Yellow. Then he introduced me to someone else, and they introduced me to someone else and then people from Chicago had seen that I was in England so like Nate Fox introduced me to Reuben James who’s from Birmingham, and then Ruben introduced me to Linden Jay.

I listen to a lot of your music when I’m running and it actually feels like a party, but the content doesn’t shy away from the harsh realities of racism or inequalities in America, how are you able to balance that?

I love movement music, like dance music. I didn’t want to make my music particularly political, but I wanted to talk about my experiences and my truths. When I was younger, I did this after-school program called the Chicago Freedom School and they had us reading like Paulo Freire, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. So, from there, I was installed to think critically about a lot of things. When I started rapping and writing, I just wanted to rap about things in a positive light, but also spotlight and shine a light on this idea that there’s beauty in the struggle, but not glorifying the struggle and not exploit the struggle which I think rap music does. I think that there are ways to do that. Like, there are ways to show this beauty in the struggle and not exploit it, not romanticise it.

- Co-Ord la boutique

I remember when we first met you was very observant, talking about the difference between Black people here and Black people there. How does that blend into the work you’ve made in UK?

Well, a lot of the music I was writing was about me being away from home and experiencing UK culture. The differences and picking up some of the lingo. I remember some lines I have I’m mentioning geezers, you know. So, I feel like that’s how I was inspired. Also, the UK gave me a second language and expanded my vocabulary. I would talk about social issues in the UK which were interesting because the UK is so upfront fascist, but also low-key in terms of like the government itself. When I landed, they were trying to pass a bill telling folks that they couldn’t protest loud. I was like, what the hell! I mean that’s crazy and the people felt like there was nothing they could do about it but protest against it. I remember I wrote a line or two about that. I think the biggest shock to me was that I knew that slavery was outlawed here in the UK, but I thought there would still be Black folks who were descendants of those slaves that were there, but I didn’t run into any of them. I think a lot of the Black folks I ran into were either from the continent [of Africa] or like their parents or their grandparents so that was like a big difference and made me re-examine my Blackness and I don’t know, I never felt so Black American than I did being around all these different Black folks from specific places because they all knew where they were from, all had connections to their lineage and their culture. I thought it was so beautiful. I am American when I go anywhere into the world and then I’m Black versus when I’m in America, I’m Black and then American, but low-key I’m just like Black to a lot of people.

Did you notice a difference from being in London vs being in Bristol and other cities?

Bristol is a little wacky, so I kind of got to Bristol and spent like a day there and I went to Bath because I just didn’t really rate Bristol so much. I didn’t feel the need to go to Cornwall and Devon as they were telling me that people in Cornwall and Devon don’t really like outsiders. I was like I can’t be arsed enough to deal with that shit. You know! When I got to Manchester and I’d open up my mouth, everyone was like, bro, we need to talk because like how the fuck did you end up in Manchester in the middle of a pandemic and what the fuck are you doing up here? I went to Hexham, I think it’s my favourite place I went to in the whole of the UK, it was just a small town, but I met so many people that were coming down to London to visit friends and then when I went to Hexham it felt like I knew the whole scene there. Newcastle reminded me of Americans the most like the way they would dress up, the way they would walk around, and even though they had totally different accents they had the most like American energy.

It’s interesting what you’re saying about Newcastle, because, you know the TV show Jersey Shore? We have our own called Geordie shore.

Yeah, I remember someone told me about the Geordie Shore.

- Shirt la boutique

- Sunglasses gentle monster

- Shirt la boutique

- Shirt la boutique

So, what other differences did you experience between the music culture / community in the UK vs. Chicago?

Well, I came as an outsider, but one thing I did notice is that people love to do more in-person sessions. In Chicago, I just do everything in my room, or I’d link up with the band and wouldn’t record things, but we’d rehearse and do live arrangement and things but like. In Chicago, you might work with like two or three people and just kind of stay in that circle… When I went to London, I made music with people in person.

You mentioned that everyone was making music in person and that being unusual for you because in Chicago you make music in you room in isolation – isn’t it funny that in a year where we’re meant to be self-isolating, and people are more separate than ever politically and socially, you had an experience where you were more social and together than you’ve ever been making music.

It’s super crazy. I realised in the States because we have bigger flats here or apartments, people especially when you go to LA, everyone has like a home studio and it’s like a really lush ass at-home studio that they’re making music out of. In London, the flats are so small and the neighbours complain so much about the noise all the time in London that everybody has a studio outside of their home. It got to a point where I was just making music and meeting new people, creating these friendships through the people I was making music with, and then when I was done making the music, I would immediately just go hit the pub and have a pint… and meet more people.

- Bag Published By

- Trousers New Look

- Shirt Song for the Mute

Did the sound change depending on where you were in the country?

I couldn’t make any music in Bristol, because they were in lockdown, lockdown. I went to Hexham and met people who owned venues and pubs and like they were like well if you tour you got to come up here and play a show. I didn’t meet too many people that did music to be fair, I don’t think there’s a lot of like rappers in Newcastle, rappers, or really good producers. The most creative scene. I mean, London was obviously London, but like, the most creative scene and the scene that was like the most shocking to me and I think had the most low-key dopest like tunes was Manchester. I made some cool friends in Manchester that make music. That whole hip-hop underground scene is really cool. The music I made there was more drum-heavy and drum-driven, a little bit more of an underground hip-hop feel.

What are you most excited about and when are you coming back to the UK?

Me and Linden J have two tracks, we probably gonna release on Defected Records as singles before the end of the summer or early fall. So, I’m excited for that. Hopefully, that happens, but if not, me and Linden are going to release something and then me and Yellow Days. I’m excited about releasing this EP before fall and then going on tour. I mean, I’m making music with everyone digitally now so I’m excited to finish these tracks and then I’m thinking that I’m gonna come back [to England] maybe sometime in fall, like in October. I was trying to come back immediately but here in the states we just opened up you know, so I mean it’s like grab a bag time you know! I think this year I’m going to try buy a house here in Chicago and kind of get settled and then once I get settled, I’m probably going to be like moving around a lot.