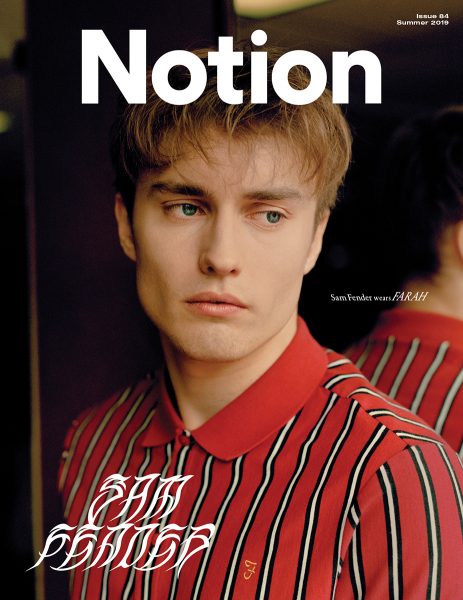

- Sam wears Farah

- Words Tom Connick

- Photography Sam Wright

- Fashion Robbie Canale

- Grooming Rebecca Barnes @ Creatives Agency

- Photography Assistant Jaime Shipston

- Fashion Assistant Rae Harrison - Doyle

- Production Studio Notion

- Location Brockley Social Club

At just 23, Sam Fender is already being hailed as one of British guitar music's next greats. It's all down to honesty, he explains for his cover feature for Notion 84!

Tucked away behind a hedgerow, just off one of South East London’s main thoroughfares, Sam Fender is barrelling around Brockley Social Club. Skipping, jumping, and beaming ear-to-ear, he breaks into near-deafening sing-song at every opportunity. You can hear his voice echoing down the hallway, bouncing off the walls. It’s a far cry from last night’s setting — the grandiose, 2,000 capacity Shepherd’s Bush Empire, where Sam’s pitched up for a three-night residency. Tickets are like gold dust; just a couple of days after we meet, two nights at the 5,000 strong Brixton Academy go on sale. Tickets to that disappear just as fast.

Those ticket sales are just one marker of a career that looks set to go stratospheric, even at this early stage. A heavy touring schedule since day dot made Sam one of the country’s most celebrated prospects, long before a 2019 BRIT Award for ‘Critics’ Choice’ came — previous recipients of said award include Adele, Sam Smith, Rag’n’Bone Man and Florence + The Machine. As a result, Sam Fender’s already being talked about in lofty terms — the next great hope of confessional, storytellers’ guitar music.

Back in the social club, though, Sam’s taking a second to look backwards. It’s places like this that a young Sam first fell in love with music, he explains a couple of hours later, energy expended. He slouches down in the well-worn booths like he’s right at home, despite being close to 300 miles from his North Shields hometown. “This is a graveyard now — all of these places are,” he shrugs, his mood dipping a little from that happy-chappy earlier self.

Sam’s dad was a jobbing musician, he explains, and would split his time working blue-collar jobs while touring the social club circuit throughout the 70s. While Sam himself might have been but a twinkle in dad’s eye at that point, the bloodline stuck at it. “Me dad’s a songwriter — he was a club player, then he became more of a songwriter in the later years of his life — my brother’s a songwriter as well,” says Sam. His household became something of a one-stop-shop for North-East England’s touring musician circuit, he recalls with a laugh. “There were always musicians coming in and out of the house — I was always surrounded by people coming in with keyboards and hammond organs and shifting speakers all the time.”

Chaotic though it may have been, that musical upbringing instilled not only a love for creativity in a child-age Sam Fender — it also hammered home a work ethic that he holds dear to this day. “They were working men through the day,” he explains of his ragtag household’s occupants. “A lot of them had trades — me dad worked the rail yards through the day — and then they would go play gigs through the night. It was a very blue-collar family by day, but musicians by night.”

He smiles at the memory. “It was a very strange, mad place. During the day you’d have Stan the gas-man working, and my dad would be plastering and working on the house and doing odd jobs — everyone just being very blokey, traditional ‘men at work’ types. Then they’d be playing clubs at night, and I’d be sat at the age of two, three — toddler age — in me highchair, just jumping about!”

- Sam wears all Farah

From there, Sam’s path seemed pre-ordained. Given his first guitar at eight, and obsessed with the thing by 10, he began writing “indie bangers” in “a shitty guitar band” as soon as he hit secondary school. From that point on, he barely put the thing down. A teenage obsession with Bruce Springsteen soon followed.

“It’s been a wonderful journey,” he says, reflectively, “but I loved it even when I was just playing buskers’ nights! I loved it when I was on the dole, and I had no money. I was living at me mum’s watching Cash in the Attic and Dickinson’s Real Deal in the morning, and then I’d go do a little gig after that.” When his mates all graduated from secondary school and evacuated the North East for uni towns, Sam found himself left behind. “I felt very alone in that town,” he admits, though he twisted it into something more positive. “I was working in a very small old pub,” Sam adds, “and I got a lot of inspiration from being in that place.”

Surrounded by — and pulling pints for — the working-class Northern families he’d grown up around, his refusal to decamp to uni (an avid bookworm, he couldn’t bear the thought of being told what to read) fed Sam’s desire to create. He refused to let that background hold him back. “Opportunity to do art is associated more with the middle classes,” he posits, “But some of the best artists in the world come from nothing. Some of the greatest of all-time – musicians, artists, writers — are just normal people.”

That gulf between the elites and working classes was the inspiration for his debut single, “Play God”, a track which painted a dystopian tale of an Orwellian mistreatment of the working class. Despite that seemingly downtrodden sentiment, though, Sam sees his background as a creative boon. “I think you’ve got more to write about. You’ve got more relatable things to write about, because there’s more normal people than there is not. People from that walk of life have a lot more to write about compared to those that are privileged.”

For Sam, that desire to connect with those he’s surrounded by manifest itself in a form of songwriting that eschews flowery language or complex metaphor in favour of something more direct. Like iPhone notes, scraps of inspiration or diary pages, all hastily glued together, his lyricism provides snapshots of an everyday mindset, free of pretence or preciousness. “I’m very matter of fact with my lyrics — I don’t try to over-flower things or make things more complicated than they need to be,” he says. “I try not to be too wordy. There’s nothing worse than too clever. If you try to be too clever it’s a fucking nightmare.”

He cites fellow Tyne and Wear band Little Comets as an example. “They’re one of my favourite bands,” he admits, “but the one thing I don’t like about them is their lyrics — they’re too clever, they use words like ‘taciturn’. No one knows what that means, or cares! If you start going like, ‘Jennifer why’d ya have to be so taciturn?’, no one’s ever said that in the history of mankind. Imagine saying that in the pub. When you write like that, it doesn’t connect with people, people don’t get it, they don’t understand.”

That reference to pub chat, and a desire to connect, cuts to the core of Sam’s songwriting. Those days and nights spent pulling pints in a pub not dissimilar to the one we’re in today remain an essential part of his musical make-up, his conversations with regulars teaching him the importance of connection. But more than just drunk chat about peanuts, or whether or not the fruit machine’s fixed, Sam’s experiences on both sides of the bar coloured a track with far greater clout.

“Dead Boys”, released last year, is a document of one of the darker sides of Sam’s hometown. The North East of England suffers from the highest rates of suicide in all of Britain — almost twice that of London, with 847 people in the North East losing their lives to suicide between 2013 and 2015. Of that total, 191 were women, and 656 were men. Surrounded by such stories on a day-to-day basis, it was a fact brought horrifyingly close to home after the loss of friends and schoolmates of Sam’s own. He dealt with it the only way he knew how — directly, and lyrically.

It’s something he approaches with typical succinctness on “Dead Boys”. “Nobody ever could explain / All the dead boys in our hometown,” he sings in the soaring chorus, before nodding to another lived experience: “Everybody ‘round here just drinks / That’s our culture.”

The track became something of an understated anthem for those struggling with their mental health across the country. Stories began to flood Sam’s social media inboxes; people were reaching out to thank him for “Dead Boys”, sharing their own stories of struggles with suicidal thoughts, or loved ones they’d lost to suicide. It was that connection he’d always spoke of, coming good in front of his eyes.

One particular story hit harder than most, though. A man named Ben, whose own struggles with suicidal thoughts had reached a head, had left his wife and two kids at home, and was driving away with the intention of ending his own life. Instinctively, he turned on the radio — “Dead Boys” was playing. Ben pulled over, burst into tears, and looked up the songs lyrics. He turned the car around, returned to his family, and sought professional help. After an email was sent to the radio station thanking both them and Sam, Ben and Sam met up backstage at Brixton Electric. Ben thanked the 23-year-old singer-songwriter for saving his life.

Tom Connick: How does it feel to have made such a tangible impact with a song?

Sam Fender: It just doesn’t matter what else I do now, that’s the best thing my music’s ever done. That is an actually positive thing that’s come from my music, therefore this was the right thing to do — my art has done a good thing.

TC: Did you ever anticipate “Dead Boys” having that kind of effect?

SF: I never, ever overestimate the importance of my job. It’s not important — we’re primarily entertainers, here to make people’s day a little bit better, or to create art. We’re not heroes — people that are heroes are the doctors, and the people out there coming up with cures for cancer, and tackling climate change, and war zones, and charity workers, and paramedics — they’re the heroes, they’re the people who are doing shit that’s important. So when there’s one small moment where a song actually connects with somebody on a level where it’s stopped them from actually taking their own life, it makes you realise, ‘Oh, maybe my job actually has a lot more clout and weight to it’.

TC: What was it like to meet him afterwards?

SF: That was surreal, but incredibly humbling. It just gave my job a little more sustenance, it made it… I don’t know what the word is. I was struggling. I think you can get bogged down by what you’re doing and going, ‘Am I having a positive impact?’ When you start getting all existential and having a bit of a crisis going, ‘What is my meaning?’ I think you need a meaning, don’t you — everyone needs one — and stuff like that gives us a meaning.

- Shirt Levi's Vintage

- Trousers Urban Outfitters

- Shoes G.H. Bass

It’s proof that an honesty-first approach can reap real-world benefits — a learning that he’s taking forward into his debut album. Finished just last week, the record is as to-the-bone as Sam’s ever gone. “When I write songs, people get on with them because I just literally say what I’m thinking. Like, in “Hypersonic Missiles” I’m literally saying ‘I’m not smart enough to change a thing.’ I’m not making any metaphors. I’m saying exactly what it is.”

That honesty has tripped him up once already, though. “Poundshop Kardashians”, a track released last year documenting the vacuity of selfie culture and celebrity obsession, came under fire from certain corners of the internet, accused of sexist tropes, with lyrics about sex tapes in particular subjected to a certain scrutiny. It’s something that clearly frustrates Sam, even today. “It got picked right apart — a song I wrote in three minutes.”

He’s not a fan of that incendiary internet culture, he says. “It’s smug liberals. People wonder why the fucking Tories are still in? The Tories are still in because the left wing isn’t connecting with the working classes, it’s not connecting with real people. I’m left wing, but it’s not connecting with the average Joe. They’re fighting all the wrong battles — far too much in-fighting.”

Sam longs for a change of focus, for his fellow left-wingers to fix their attentions on bigger issues than semantics. “The planet is dying, we’ve got ten years before we kill the whole thing and fall into a chain reaction, or whatever. We have got inequality, and that needs to be sorted out, but we need to mobilise the left and mobilise people to get the government to tackle climate change — which is probably the biggest problem we’ve got.” He compares the situation to the ever-growing class divide in Britain. “That whole liberal, snooty, over-analytical, over-clever, arrogant left, they alienate working class people and make them feel stupid for having a different opinion.”

Besides, he says, away from the internet, there’s a far more direct reaction happening in front of him, night-after-night. ”Poundshop Kardashians” didn’t mean much to us, but I play it in the set because the kids like it,” he says. “Why the fuck should I give a fuck what journalists are saying, when two-and-a-half-thousand kids in Shepherds Bush sang every word to it last night? I don’t think they’re sitting back and going, ‘Yeah, he’s a misogynist, let’s all be misogynists!’ I don’t think they’re thinking that for a moment. They’re actually just singing it because it means something to them.”

The connection he’s made is impossible to ignore, after all. “People like a bit of honesty,” he says. “People respect honesty and they respect saying it how it is, or how you think it is. I get it wrong sometimes — as I say, I’m not a genius, I don’t know enough about economics or politics to have an opinion that’s different to anything that’s been said before; nothing that’s particularly original. But that 23-year-old at the time, who was looking at the telly going ‘What the fuck’s going on?’, I just turned that into a song. I think people can relate to that. The only thing that I’ve done is make something that a couple of people clipped onto, and they’ve gone, ‘Oh yeah — that reminds me of me’.”

- Sam wears all Farah

With that debut album fast-approaching, all Sam’s promise looks set to come good. He’s excited to get more material out — further opportunities to connect — and to hit the road all summer, and long into the future. Those opportunities for real-life, whites-of-the-fans’-eyes connection are racking up, after all. As the afternoon sun starts to creep through the hedgerow outside, he’s already looking to the future. He breaks into song once more as his publicist orders an Uber to yet another sold out show over on the other side of town.

“You can’t dictate what they’re going to pin you as,” he says with a smile, moments earlier. “I’m just going to make records and play piano and guitar and whatever I can play and they can call me whatever they want. ‘White boy with guitar — here comes a fucking ‘nother one!’,” he adds with a laugh.

I’ve got a lot of directions I want to go in — there’s a lot of things I want to do with my music. I don’t want to stick to one thing. A lot of this record is quite indie; the next one I want to do that heartland rock-y, more Springsteen-y sound.” He whips out his phone and plays a demo he’s already begun penning for album two, all stabbing piano chords and theatrical delivery. The Boss’ influence is undeniable.

It’s an interesting admission, and perhaps a wise move, from a singer who’s already been dubbed a next-gen Springsteen in some corners. That’s one press clipping he’s more than happy to laugh off, though.

“It’s just stupid! It’s just daft,” he grins. “I love Springsteen, but I’m never ever going to compare myself to that. He’s one of the greatest songwriters of all time. I’ve definitely not written a song that good and I probably never will… but I will try.” He breaks off with another beaming smile: “I will try and be a poundshop Springsteen.”

Order the Digital Issue of Notion 84 here!