- Words Joe Zadeh

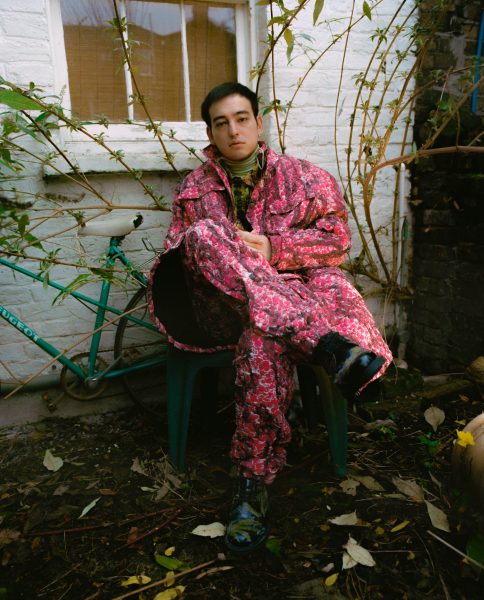

- Artist Joji

- Photography Erika Bowes

- Fashion Caitlin Moon Curran

- Grooming Ana Takahashi

- Fashion Assistant Zahariah Demelo

- Production Studio Notion

- Videography Candice Lo

Joji is the contemplative crooner that’s turned YouTube notoriety into Billboard conquering chart stardom via his debut album Ballads 1. He’s known around the world for two reasons, but he wants everyone to remember him for a third.

I am here in this 1,625 capacity London venue—Heaven, they call it. Well, Heaven is full of screams. Deafening screams from all around me. Sharp and shrill. A school of teens in dungarees and vintage Umbro harp impatiently. There’s a gaggle of glittery top girls too, mixed into a clowder of Kappa tracksuit boys with shotter bags round their torsos. What do you call a group of blue rinsed emos draped in hanging chains? A murder? There’s a murder of them, as well as some goths in black cut off denim. Lastly, there’s a shrewdness of checked shirt bearded blokes with badges on their beanies, a romp of white girls with braids and words like “LOVE” written on their t-shirts, and one woman, standing alone, dressed head to toe in Christmas lights.

They queued around the block for this show, as early as three hours before doors, and now they are inside and the show is starting and we are all screaming. All of us. Except the checked shirt bearded blokes with badges on their beanies, they are just swaying, but I can tell from their contrived faces that somewhere inside they are hysterical. I don’t recall seeing an audience this diverse and this animated at many London shows. Maybe I don’t go to enough shows, maybe it’s because everyone wears anything and listens to everything nowadays, or maybe it’s down to the far-reaching appeal of the man onstage, who, in this moment at least, goes by the name of Joji.

Joji is a brand new artist of seismic popularity. His debut album, Ballads 1, rocked in at number 3 on the Billboard chart (No. 1 on Billboard’s Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart), and the first single, “Slow Dancing in the Dark”, scooped 91 million streams and counting on Spotify. To put that into perspective, that is just ten million less than “Yikes”, the lead single from Kanye West’s recent eighth album, ye.

While his music on Ballads 1 is inherently beautiful, it isn’t exactly the most accessible sound in the world. At heart, Joji is very much a 21st century bedroom producer, making moody and intoxicated lo-fi beats with a gritty and enchanting atmosphere. He can sing too: his lyrics are melancholic and psychosexual, and he delivers them in slurred, pained tones. Venereal hooks like “Does your tongue still remember the taste of my lips?” bob and float around your mind like a rubber duck. Each song has a kind of aqueous fragility like they might evaporate at room temperature. And the piano arrangements are so intensely gentle, you can envision him playing them with his little toe or perhaps just blowing on the keys. Joji, I imagine, is how James Blake would’ve sounded if he was born in 1998 instead of 1988.

- Jacket HENNA HERVA

- Top HENNA HERVA

- Jacket HENNA HERVA

- Top HENNA HERVA

Watch any of his high concept music videos from the last 18 months and you’ll see that the Joji aesthetic is like that of a well written character from a stylish film noir. His face is often devoid of expression, his mouth moves languorously, like he’s speaking to you from the midst of a xanax fuzz, and he does long lingering stares into unseen nowheres. He’s often physically hurt or injured in his videos, walking like a fawn would for the first time. In “Test Drive” he hangs on a chain from the sky, his arms strapped up in a straitjacket. In “Slow Dancing in the Dark” he has been gored in the back by an arrow, blood spreading across his white tuxedo jacket, and yet he continues to suck at a rain soaked cigarette.

Two days prior to the show at Heaven, I met Joji (real name: George Miller) in a pub in West London. There were barely any tables left so we sat in the only one nobody wanted, a table so close to the roaring open fire that we may as well have been in it or on fire. “Yikes,” says Miller as the barman walks over and throws yet more coal and logs onto the spitting inferno, as if the pub were a steam train he needed to keep chugging all the way to Gretna. Joji ordered some water and took off his hoody; underneath he was wearing a green ‘Lucky Charms’ t shirt. “I don’t usually come to pubs much because I don’t drink anymore,” he says, “I try not to have caffeine either.”

Miller has a hyperactive visual imagination. “Sometimes it’s too visual,” he says, “because then scary thoughts are way more vivid. And that is what fuels a lot of my music too. A lot of it is me just keeping myself busy, not wanting to pay attention to too much.”

“Because?” I say.

“Because otherwise it goes a little crazy,” says Miller.

When he writes songs, he immediately sees the scenes that will become the videos. In fact, if he doesn’t conjure these visions while working on an instrumental, he’ll scrap it and start again. Take the video for “Yeah Right”: he was feeling morose when he made that song, but also weirdly excited. “I put that feeling into the instrumental and I immediately saw the video,” he says, “girls twerking on someone too depressed to pay attention, sad disco ball lights—I saw all of it.”

Sat on a table behind us is Miller’s bodyguard, a Mustang of a man with long auburn dreadlocks and tattooed hands. I’m told he also worked as security for the former heavyweight boxing champion Tyson Fury and the nu metal godfather, Fred Durst, which explains why his jacket read “Limp Bizkit Crew 2016”. I’ve never interviewed anyone who required a hench security guard to be sat on an adjacent table, but maybe I’ve never interviewed anyone as famous—and for so many different reasons—as George Miller.

Miller was born in the Kansai region of Japan, to a Japanese mother and Australian father. His earliest memory is almost drowning in a lake by a dock after watching an eel dance in the water. After that, childhood was calm. He’d go out catching fish and bugs—cicadas mostly, but one time it was a huge praying mantis—and exploring the nearby mountains. At school he was mischievous. “If someone had drawn a penis on the board, then everyone would turn around and look at me,” he says. In the evenings, he’d sometimes watch replays of old American cartoons like Charlie Brown and Garfield. That cat was a piece of shit – “Well done, John!”, “Nice going, John!”—but Miller loved that about him.

His friend’s older brother would pass on vinyl to them. First came the new metal bands, Limp Bizkit and Korn, which became a gateway into boom bap and early 2000s rap. Then in sixth grade he heard “A Milli” by Lil Wayne. “I thought the beat was so game-changing. I went home and got on GarageBand and re-made the beat. I was rapping on it with my friends and stuff. And they were like: how did you do this? I still use GarageBand to this day.”

- Jacket, Jumper, Trousers Anni Salonen

- Top StrongThe

- Shoes Henna Herva

In Japan, Miller was seen as white, thanks to his Australian side—“White boy, white boy, whassup?” his classmates would say to him. When he moved to America at the age of 18, it flipped to “What up, Asian?” “So I’m like: okay, I’m nothing then,” Miller tells me. “I was stuck in a weird position where I didn’t fit in too much. I heard friends say they can’t wait to go back to their ‘hometown’, their ‘old stomping grounds’. That didn’t exist for me.”

You know that Harlem Shake meme that went global in 2013 and was co-opted by everyone from the Miami Heat basketball team to the wrestlers of WWE, and helped the original song hit a billion views quicker than “Gangnam Style”? Miller started that. He was 19 years old, living as a student in New York and uploaded a video of him and his friends dancing to the then underground song, “Harlem Shake”, by Bauuer. He’d uploaded it to Dizasta Music, a YouTube channel he’d started at the age of 12. It launched a trend online that, three days later, became a worldwide phenomenon.

He has a knack for things like this. In the world of YouTube, Miller is notorious as both a scourge and a legend, thanks largely to a webshow he ran for six years (beginning in 2011, at the age of 19) called The Filthy Frank Show. The show centred around its main protagonist, Filthy Frank (played by Miller): a racist, misogynistic, homophobic, perverted, violent and pathetic character who spoke with a grating voice, wore cheap spectacles and a (often stained) blue collared shirt. The show would involve skits, rants and public pranks. It was like a DIY hybrid of Jackass, Rotten.com and Ren & Stimpy. Frank was the anti-vlogger and the ‘idea’ was to offend everyone—as exemplified by his raison d’etre: “We need more prejudice equality, everyone gets shit.”

His fanbase grew into the millions, full of viewers who either found him too funny or disgusting to look away, or felt it was genuine performance art for the internet age. New characters were added (usually played by Miller or friends) and a mythology built around it, known as the Filthy Frank omniverse. At a time when YouTube was trying to clean up its act and become more of a Disney-esque environment, Frank was racking up millions upon millions of views for videos in which he ate cakes made of vomit, cooked dead rats, and insulted pretty much every nationality and ethnicity in the world. In one of the most popular videos on the channel, titled “100 ACCURATE LIFE HACKS”, Frank’s final life hack sees him attempting to kill himself with a shotgun pointed into his mouth. Ethan Klein—one of the biggest commentators and personalities on YouTube—has called him the best YouTuber of all time.

In a written section on his YouTube channel, Miller had said that the idea of the show was to expose how easy it is to gain a following online simply by “sharing unsavoury opinions and joking about topics many find offensive.” Just like with successful US TV shows like The Colbert Report (in which Stephen Colbert played the role of a blustery right-wing pundit), the idea of Filthy Frank was to espouse the extreme opposite views of its creator, and “be the embodiment of everything a person should not be.”

But just like with Colbert (a 2009 study by Ohio State University found that most conservatives believed Colbert was not satire and actually held those views), there were often Filthy Frank fans who sympathised with his extremism. Miller acknowledged this in 2015 during an interview with Anthony Fantano for The Needle Drop podcast, noting that some fans seemed to love everything until Frank’s crosshairs turned on white people: “I remember as soon as I made a white [people] joke, something about rednecks fucking their sisters or something, everyone lost their shit and started making these really passive aggressive comments.”

- Dungarees Walter Van Beirendonck

- Top Walter Van Beirendonck

One of his most loved characters was Pink Guy: a pink lycra wearing creature who spouted gibberish all of the time unless rapping, at which point he would spit over fairly impressive hip-hop instrumentals (all produced by Miller). Looking back, it almost seemed like Miller, who had always aspired to be a musician, felt the only way he could achieve it was by getting in a morphsuit and cracking jokes about it on the internet.

“I’ve always wanted to make normal music. I just started the YouTube channel to kind of bump my music,” Miller told Pigeons & Planes in January 2017. “But then Filthy Frank and the Pink Guy stuff ended up getting way bigger than I thought, so I had to kind of roll with it.”

When Pink Guy released a mixtape in January 2017—titled Pink Season, and featuring songs like “Rice Balls”, “Please Stop Calling Me Gay”, and “I Will Get a Vasectomy”—it entered the iTunes chart at #2, beating the soundtrack for La La Land. Miller even wrote a book explaining the lore of Pink Guy and everyone else in the Filthy Frank omniverse, titled Francis of the Filth, and published it in September 2017. It reached #47 on USA Today’s bestseller list.

- Shirt Pronounce

- Jewellery Joji's own

But that same month, he stopped posting on the Filthy Frank YouTube channel, stopped using the related social media pages, and has since tried to distance himself from that period of his life. When I bring it up in the pub, he looks uneasy if not unsurprised. “It must come up in a lot in your interviews?” I say.

Miller: “I understand why. That’s what makes this whole thing so great. This guy is now this guy? It’s fucking crazy. It’s two completely different things,” he says.

“How does that make you look at the past?”

Miller: “No regret or anything. Just like, that was a time. Now is a different time. The chemicals are moving a different way now. It’s moving a whole different direction.”

In his farewell post to Filthy Frank fans on Twitter, he said “I no longer enjoy producing that content” and that he had developed serious health issues that included throat tissue damage and a neurological condition. A photo of him on a hospital bed with sensors and bandages all over his head began to circulate. When I ask about the specifics of the condition, he prefers not to say too much, but from other interviews I learned that it causes stress-induced seizures, requires daily medication, and means he cannot be alone for prolonged periods of time.

“That sounds like a life-changer,” I say.

“It was the only and biggest changing point,” says Miller. “Immediately after that, my whole mentality changed. I stopped touching social media. I only cared about what I cared about. Life is short. I used to hate animals—not hate but I was just like, whatever—but I started falling in love with animals. I started playing with cats and dogs. I became so much happier. As my health got worse, I learned to appreciate the things around me more. I became a kinder and more understanding person in all aspects. As much as I hate to say it, in a lot of ways [the neurological condition] was a gift. I like the way I live now.”

The way he lives now is not as Frank, Pink Guy or even Salamander Man, but as Joji, the musician. He’s signed to the soaring record label, management team and collective known as 88Rising (alongside Rich Brain), released his debut album, Ballads 1, and collaborated with the likes of Clams Casino, Ryan Hemsworth and Shlohmo, artists he fantasised about working with as a teenager. He has a level of control in almost every aspect of the Joji project, from the songwriting and production to video editing and directing, and even the album artwork. But the ghost of Frank still lurks, if you look for it: seven of the top ten most popular comments on his biggest music video on YouTube are fans referencing Filthy Frank.

- Waders, Jacket Walter Van Beirendonck

- Neck Piece Anni Salonen

“A lot of Frank fans still seem to be mourning his disappearance,” I say.

“I’m sure they are,” he says. “It was a big part of a lot of people’s lives. I’m sad too, I guess, in a lot of ways. But time goes on. We are forever victims to the forward marching of time. There is no escaping it.”

As the live show at Heaven draws to a close, Joji decides to finish on his most successful single, “Slow Dancing in the Dark”. It’s a romantic and otherworldly song, and perhaps the closest he’s come to his ambition of reinventing the perfect ballad. The music video plays on screens behind him, and red neon stage lights pulsate slowly with the beat. As the chorus approaches the crowd becomes an overgrown meadow of raised fists and lofted iPhones. “In the–” sings Joji… “DAAAAAARK!” screams the audience.

Then the song ends, the show ends, the lights go up and people begin to disperse. I wander to the front, where the most die hard fans can usually be found, and see an assortment of teenage girls trying to give roses and handwritten letters to the techies, begging them to pass them on to Joji. On the now empty dance floor, a guy in his early twenties, drunk and seemingly in search of his friends, staggers and kicks his way forlornly through piles of discarded plastic cups. He’s dressed, head to toe in lycra, as Pink Guy.