- Words Colin Gannon

- Photography Aidan Zamiri

- Styling Kamran Rajput

- Grooming Lauraine Bailey using Tropic Skincare & MAC

- Production Fernanda Dugdale for Studio Notion

- Photography Assistant Nathan Perkins

- Fashion Assistant Misha Pishalnik

- With Thanks To THRDS & LASSCO Ropewalk

- Production Assitant Bliss Zhawi

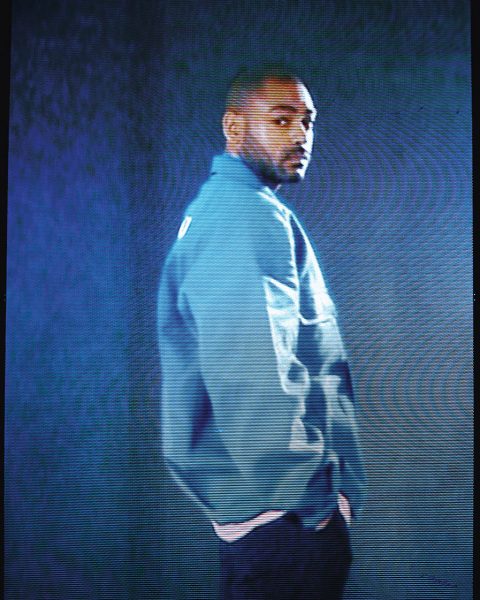

Fifteen years since he first stepped into the ring and fresh off the back of his electric Wray residency live show with iconic rum brand Wray & Nephew, the rapper and actor reflects on his personal growth, Jamaican roots, and community in Notion 87!

Top Boy’s Sully is by no stretch of the imagination a fictional character to aspire toward. Prone to acts of deadly recklessness, his is a difficult temperament to get right, especially for an inexperienced actor. Aside from Sully’s dogged persistence, though, Kane Robinson recognised very little of himself in his character’s personality.

“At times when I had no reference in my own life, I would try to call someone who had,” he says. “I was speaking with some of my mates who are in prison, trying to tap into their head a little bit.”

Kano’s first and arguably most momentous camera appearance came in 2004, when he and ‘godfather of grime’ Wiley clashed in grime MC Jammer’s now-consecrated, graffiti-scrawled basement, as part of the vaunted Lord of the Mics DVD series. The clash shows Kane Robinson coming into his own as Kano: aggressively rhyming toward the camera, his daggered lines tumbling into one another; the then 18-year-old’s hands flailing and head bobbing in rhythmic motion, a cheeky, cockney glint in his eye.

When the somehow-still-fresh-faced 34-year-old laughs, it’s hearty and wheezy, filling the entire east London photo studio in which we’re perched. Beginning first with his latest album, and ending with the importance of home in grounding him, the only time his attentive gaze wanders is to accept a cup of coffee, mannerly and appreciatively, from one member of his handlers.

When we speak, he’s still doing the victory lap for his sixth studio album, Hoodies All Summer. His most ambitious release to date is an elevated version of the things that have become his signatures in recent years: dextrous flows, hyperspecific lyrics, genre swashbuckling, conceptual depth, and unexpected sweeps of live instrumentation, all delivered with a tasteful touch of nostalgia.

When they’re not grime speaker-busters, his songs are often diaristic, like they’re written alone in the dead of night. But naturally enough, Kano’s fame—and his recognisability in circles outside of grime and music—has skyrocketed since the release of 2017’s Made in the Manor. In the intervening time, he has filmed and basked in the glory of his close-to-home reprisal of Sully in Top Boy—the unremittingly violent gangster drama resuscitated by Drake for a third series on Netflix after being dropped by Channel 4. The show most closely resembles David Simons’ Baltimore-based show The Wire, particularly in its panoramic portrayal of the impoverished ecosystems undergirding modern cities like London, the everyday living monuments that never get Instagrammed by tourists, nor idealised by the advertisement industry.

- Top Liam Hodges

- Top Liam Hodges

This sparked the inspiration for Kano’s triumphant Wray Residency show at Newham Leisure Centre in February, where he used to go to trampolining class back in the day. Teaming up with iconic Jamaican rum brand, Wray & Nephew—who collaborate with musicians, like Ms Banks and Gaika, to commandeer unusual spaces for one-off gigs in their local community—together they brought a 26-piece orchestra to the heart of Kano’s home turf.

Dishonestly written British cop dramas are no match for the granular human tragedies on the show, which saw Kano embark on one of his best, and most urgent, performances of his polymathic career, whether on-screen, on-stage, or behind a mic. His music does, however, offer something similar: treatises not only concerned with what devastates entire communities, but what devastates the individual. Addressed to a half-sister who he hadn’t seen for so long that he’d actually forgotten she existed, “Little Sis”, off of his last album, remains one of his most achingly personal songs to date. They ended up coming into contact, reuniting at a live show months after the album’s release. Prior to this, he was openly fretting in interviews about the song’s release, afraid of what unintended ramifications might ripple across his life in the song’s wake.

“I wouldn’t say I like doing songs like this—some things are just on your chest and you just wanna get it out and then sometimes you feel scared afterwards but I feel like, as an artist, you can’t be fearful. You have to be fearless,” he says, between two cautious sips of his coffee. “And I think that’s what art is about: brutal honesty. Baring all, and maybe affecting somebody, or affecting your own life in some way. That’s what it’s about.”

Kano’s music career began in earnest less than a dozen miles away from where he’s sitting today. A close friend, Demon, who lived round the corner from him, had introduced him to MCing, with the pair later going on their first tour together as a support act for The Streets. (“Stranger” on Made in the Manor details the story of their friendship and, latterly, their acrimonious falling-out). These were the opening chapters in a kind of story you don’t hear very much anymore: Instead of going viral online from one catchy, immaculately-timed hit, Kano went viral IRL.

Born Kane Brett Robinson in East Ham in London, Kano was mostly raised alone by his Jamaican mother, who worked as a PE teacher at a local school. Early on in his life, he showed promise as a footballer, taking trials with Chelsea FC and Norwich FC before, eventually, losing interest in sport. He got into freestyling around the time he met Demon, but after his mother bought his older brother a set of decks, where he spun his self-produced garage songs, a young Kano became obsessed with crafting verses.

Years after these playful, bedroom-based lyrical experiments, Kano recorded the song “Boys Love Girls”, which he showed to a young Dizzee Rascal, who helped him polish the track in a professional studio. Here, he sounded as much like a young Eminem than any English MC that came before him, slipping into the same pockets as the Detroit provocateur—rapping haywire one moment, slower and more forensically controlled the next. This was to be his first-ever single, and it was a roaring success, earning tons of airplay on iconic pirate station Deja Vu. It wasn’t long before he became a member of grime collective N.A.S.T.Y Crew, widely considered as some of the pioneers of the ascendent genre, counting among their members local legends such as Ghetts, D Double E, and Jammer.

He later signed a record deal with the now-defunct 679 Artists label as a solo artist, releasing his debut album, Home Sweet Home, there in 2005. Like many UK artists who place on the grime-rap continuum, it is both counterintuitive and reductive to describe Kano as any one of the following: MC, grime MC, grime rapper, rapper. He’s all and none of the above: an artist who emerged from grime’s clashing culture but happens to make questing, rhyme-based music that doesn’t fit neatly into any of these constrictive perimeters.

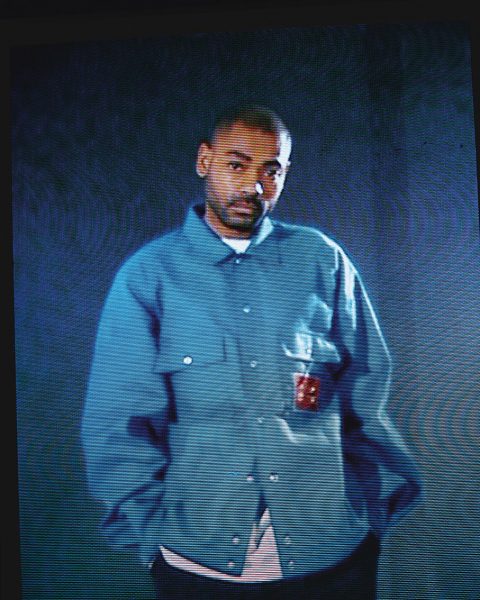

- T-Shirt Prada

- Jacket Gucci

- Jacket Gucci

- T-Shirt Prada

- Jacket Gucci

- Trousers Emporio Armani

The music on his new album, Hoodies All Summer, is as ambitious as the man behind it. Kano admits that it has sparked a different kind of adulation among fans compared to some of his past projects. During his second wave of shows following the album’s release, as he made eye-contact with faces in the crowd—especially those slammed against the railings in the front-row—he noticed they were screaming for certain songs, ones he didn’t anticipate to be in-demand at live shows. Slower, more meditative tracks such as “Teardrops” and “Got My Brandy, Got My Beats”, not your archetypal rap-grime bangers, were now showstoppers. “[Hoodies All Summer] is just one of those albums that gets into your skin, you know what I mean?,” he says, clenching his fist slightly. “It’s one of those albums you have to listen to for a while; it has definitely grown with people.”

Recorded with longtime collaborators Blue May and Jodi Milliner, the album criss-crosses genres he grew up with and came up on: hip-hop, dancehall, garage, jungle, grime. Throughout the album, this autobiographical sound template does a lot of the heavy-lifting when it comes to narrativizing, with different genre nods helping to distinguish distinct moments in time from his life. He started making the album three years ago, after a break following his tour for Made in the Manor. In fact, the new album feels like a companion piece to his last, building on its minimalism, vividly narrowing his lyrical focus on the human costs of racial inequality and unfettered gentrification.

Throughout Hoodies All Summer, which imagines the hooded garment as a kind of uniformed armour for young black men in harm’s way of a destructive British society, Kano deals even-handedly with social issues, its songs rooted in knotty emotions. On “Good Yutes Walk Amongst Evil”, an austere, manically bassy grime track, one line in particular captures the crushing conditions working-class people of colour face in estates in cities like London: “Warfare with nowhere to run to.”

Kano’s pithy writing here conjures images of powerless youths, refugees-but-not-refugees, unable to go anywhere because the wars they might wish to flee—the endless economic and social wars being waged on their bodies, their housing, their welfare, their existence—are not considered legitimate by an uncaring, elitist class of politicians and journalists. I ask him if this is a fair analysis. “In a sense, but it’s like that feeling of being trapped. Not trapped as in you can’t leave…,” he says, trailing off. Rooted, I offer? “You’re rooted; this is home,” he continues. “Dysfunction, and love, and negativity, but then optimism, and resilience, all in the one place. It’s what we call home. So, younger kids, who are involved with stuff, must really feel like they’re in a warzone they’re not even capable of escaping from—or not even trying to. It’s important for people to remain and try to make this place better.”

This, I say, reminds me of the theory I have about drill music, another sound pioneered by alienated young black men from deprived parts of London. Although drill rappers don’t use the didactic language of a Dave or a Stormzy, their mere existence, from some of the most deprived areas in the country, make it the truest and most vital political music in Britain today. Are fear-mongering headlines about drill, and the attempts to censor artists, signs that it speaks certain uncomfortable truths?

“It always feels like that with black music. Once it achieves a level of popularity, it breaks out of the estates it comes from, and it’s immediately [met with], ‘I don’t agree with this; ban this’,” he says. “If that’s someone’s true experience, that 100 percent should be validated, and it should be okay for them to voice whatever opinions they have after the lives they have lived. I don’t like people faking it, doing it to sell records even though they haven’t really lived it. But what do you expect these kids to do for a living?”.

As well as spotting the parallels between drill and grime (“To see a music scene grow like drill is really a testament to resilience, our resilience.”), the YouTube videos replacing pirate station broadcasts, the quaking basslines intact, Kano identifies something uplifting in the melting pot sound wildly popular with young people in England today. Made famous by artists like J Hus and Kojo Funds, who features on Hoodies All Summer, a formless mix of afro-bashment, afrobeats, drill, grime, and rap, Kano believes, plays to the strengths of the London he knows.

- Top Liam Hodges

“It says: we’re stronger together. It was never like that when I was really young,” he says. “You listened to hip-hop, or you listened to garage—there were different camps, and people older than me say it was even more genre-segregated before. Just to hear artists now, whether their background is Caribbean or African—inspired by both, especially the younger kids who grew up on what we were doing, as well as American hip hop—but it still never loses anything; it has a strong identity. It is London.”

In reality, Kano’s music has its own spirit of cultural bricolage, folding his Jamaican heritage into Englishness. As a youngster, his mum would take him to her homeland for months-long holidays, where they visited extended family. Recalling the time he spent reconnecting with his family roots, he cracks a wide smile.

“I’ve done a lot of my growing up in Jamaica as well as London. When you’re young and starting to go out by yourself—to the barbershop, to the local shop—I’ve done those things in England, and I’ve done those things in Jamaica, too,” he says. “Going to clubs, discovering music—I was kind of doing that here around garage music and everything else, and I was also doing that in Jamaica on holidays.”

In his music, the many Jamaicanisms—the patois dotting his lyric sheet, as well as the references to curry goat and dancehall artists like Buju Banton—are never overshadowed by a palpably grotty sense of inner-city Englishness. Camden Town, pink Ralph Lauren polos, Daily Mail paparazzi, pub culture, Premier League football—his music and persona are as unavoidably English as almost anything in popular music outside of laddish indie. But how does he like to identify himself?

“It’s a difficult one,” he admits. “I’m definitely a Londoner, but even some of my other friends with Jamaican backgrounds, who grew up in different parts of London, hear way less cockney English because we’re from East London, Canning Town. It was very that. Mum caught a bit of that, so that’s what we grew up on as well. My friends from South London ain’t eating pie and mash all day, but we kinda were.”

Kano tends to restrict his personal life to his music, and is reluctant to talk about some vague, major life changes during the conversation. When I bring up the state of British politics, though, his shoulders stoop and his eyes glaze over. You can almost hear the brain neurons racing behind his eyes as he readies himself to answer: He had avoided political endorsements until last year, when he and a group of artists came out in support of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour. Politics in the UK, he acknowledges, are “a bit of a mess”, and the election results were “a real eye-opener”, admitting that he probably lives in a metropolitan bubble in London.

“It’s been blow after blow—Brexit and everything—and it feels like a lot of these actions are against everything I thought I loved about this country,” he says. “But that’s me coming from London. It’s just that togetherness, that abrasiveness, that heart, that community—I still think that’s important.”

Do resounding political realities mean he now wrestles more with his national identity?

“As much as I am British, when you ask that question, I do think of things like the Windrush scandal, the people who thought they were British,” he says. “My mum’s not got a British passport. You feel like you belong, you feel welcome, and then—although it obviously doesn’t affect me because I was born here but it does affect my family—you do realise: Do I really belong?”

Kano prides himself on his authenticity and his artistic control, insisting on a number of occasions that honesty is the premier currency in artforms like rap. Accompanying his last few albums have been short fly-on-the-wall documentaries, which include beyond-the-scenes footage of studio sessions and context to album references and themes. These mini-films are less marketing ploys than they are auxiliary components to his narrative, to his artistic journey. Rather than overlaying his vocals over beats sent by producers online, Kano functions as the bandleader in recording sessions. Grainy videos capture an in-the-zone Kano in his element: at the heart of the collaborative process, as technically adept and musically-literate as anyone sitting behind the monitors.

- Jacket Gucci

- Trousers Emporio Armani

- Jacket Gucci

- T-Shirt Prada

- Trousers Emporio Armani

- Jacket Gucci

- Trousers Emporio Armani

He started off his career, after all, making beats, which includes producing his very first song. “There’s a couple of things that bother me,” he says, sitting upright. “When I hear people do interviews for albums, the interviewer always asks the artist: ‘So, who’s featured on the album?’. I’m sitting in front of you, and you’re worried about who else is on my album? Or when the production is good, it’s always ‘beat selection’.”

Some rappers will either hand-pick from beatpacks, or turn to others for production guidance, I add, completely trusting others to look after this side of their art for them. “I feel like a true artist has to be [at the centre of the process]. Some people have their guy, and they can just trust them, but, as far as I’m concerned, how could you not be a part of every process?”

In the music video for “Can’t Me Hold Down”, Kano brings Jamaican dancehall star Popcaan around his aunt’s house, where friends and family of Kano eat and drink decadently. “You can just see the heart in it,” he says, perhaps summing up his entire ethos. He and his crew attempted to rent a house to shoot the video, whose frames unfurl charmingly like a family photo album, but struggled to find somewhere large enough that would allow loud music and a late check-out.

“It was literally the day before, and I was like I’m gonna ring my cousin, who said to ask Maxine, my aunt, and I thought, ‘She ain’t gonna have it’. So I rang my mum. She said, ‘I’m at a funeral right now, and Maxine’s here!’,” he laughs. “I told mum to ask Maxine—maybe to add it as a little joke. And Maxine said yeah, so I told mum to tell her we’re all coming in two days time. Some things just happen like that.”

Kano comes alive when considering home. The day after Kano’s biggest live show at the cavernous Drumsheds venue in north London, he brought the same set-list and stage production to the intimate show at a leisure centre—an old haunt he used to frequent as a boy—in his home borough of Newham as part of Wray & Nephew‘s Wray Residency.

“Newham Leisure Centre where the girls at,” he raps on “T-Shirt Weather in the Manor”, taken from Made in the Manor. “Hair gelled down to her face where the curls at.”

From the leisure centre’s makeshift stage, he spotted two aunts—Dorothy and Jennifer—who are also mentioned in the song’s first verse. Kano’s uncle, who had never been to a show of his in his life, stood proudly at the back of the venue, along with familiar faces from his old estate. He was here in February, in his home borough, for an intimate show as part of Wray Residency series.

“That community spirit, that coming home, that leaving home, travelling the world and achieving big but never forgetting where you’re from,” he concludes, shaking his coffee cup from side-to-side to make sure the last drop has been drunk. “But it’s not about a memory; it’s about being visible, letting people see you. Being a role model is very important.”

Wray & Nephew’s Wray Residency series continues in 2020, visiting local neighbourhoods to bring real, raw and inclusive access to high energy, musically-charged experiences for the community. Find out more @wrayandnephewuk on Instagram or visit www.wrayandnephew.com