- Words Russell Dean Stone

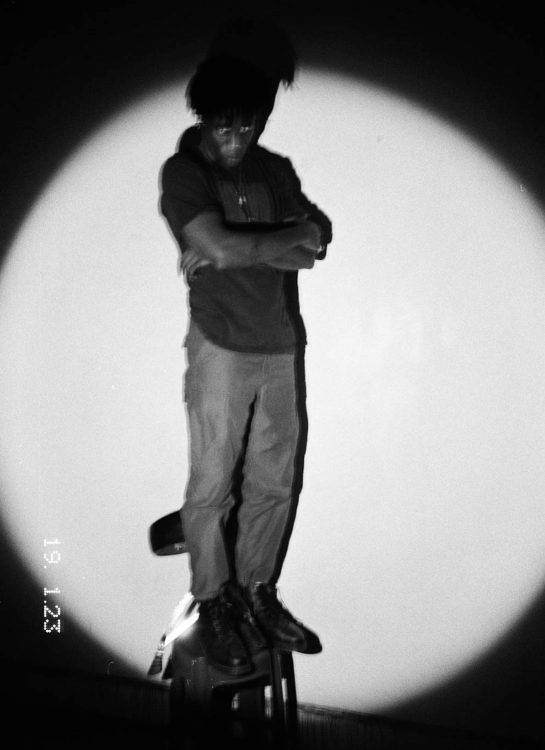

- Photography Duncan Loudon

Obongjayar is the British-Nigerian artist conjuring cross-cultural spirituals.

Steven Umoh Jr’s journey to becoming the artist known as Obongjayar (pronounced Oh-bong-jai-er) crosses two continents and is, at its core, a quest of faith, identity and finding your authentic voice.

Born in Nigeria, Umoh’s first forays into rap were part of a trio who called themselves Kensten3. Religion and American rap were primary influences on young Umoh. Kensten3 would spit religious rhymes in church, the first one Umoh can remember them writing went something like this: “We’re the Kensten3 back in town again / to get the revolution started again / to preach the gospel to the people in the world out there uh.”

Back then midnight phone calls were free, so Umoh and his friends would call up girls from school and talk in fake American accents in a bid to impress them. “If you had an American accent you were desired,” explains Umoh, “which is fucked up!” This was before the Lagos music scene exploded with the likes of WizKid were flying the flag for Afrobeat—instead 50 Cent and Snoop were the only relatable rap role models.

“It’s almost like a colonial thing,” Umoh offers. “That was the era I grew up in and the music represented that—all the rappers in Nigeria were sounding American so I emulated that trait too. It’s an inferiority complex, you think you’re not good enough because of the situation you’re in—trying to be something else to escape where you are.”

Raised by his grandma in Calabar, a port city in southern Nigeria, Umoh’s mother fled to the UK with no money, to start over and escape his abusive father. At 17 Umoh would follow her to the UK, winding up in suburban Ashford, Middlesex where he’d go to college. Umoh doesn’t remember the day he landed on UK soil, but he does remember consciously trying to “keep it cool”—reflecting on it now he acknowledges it was a seismic shift that scared him:

“The type of person I am, I’m able to move on very quickly. I don’t have any nostalgia for anything, I just go one direction—forward—I don’t look backwards. Things are constantly changing, nothing’s going to be the way you remember it being.”

At 19 Umoh moved to Norwich to go to university. He still had music on the go and even went through a short lived phase of playing in a band. In college Umoh had once been trying to be something he wasn’t, in a bid to fit into his new environment—“You want to fit in with the cool kids, wanna be road”, he says by way of explanation. University exposed Umoh to a more diverse crowd of friends, putting him on a path to personal and creative enlightenment.

“You start looking inward,” he says of this time. “You start to see things and you see how being true to yourself is the only thing that gives you an edge because no one else can do what you do—you’re the only person who can walk the way you walk comfortably, you’re the only person who can speak in your accent comfortably. People are interested in what you have to say and you are the only source they can get that from. It made me think—why am I trying to copy this or trying to sound like that when I can just be myself.”

The voice that Umoh found turned from rap to spoken word, shedding the American affectation of his previous efforts and unearthing a gritty and guttural new voice of truth. This new sound was first evident on 2016’s Home EP, before landing fully refined on 2018’s four-track Bassey. Sparse, haunted soul and damp looped samples give way to drum-led tribal rhythms, gospel and afro inflections, darkly electronic sorcery and commanding melodies led by emotion, that seem to summon Umoh’s roots at every turn.

“I still find it difficult because my mind has been trained to do this American rap—hence why I left rap and went more of the spoken work route because you can speak it in your tongue. When you say something in your tongue, that is definitely empowering,” says Umoh.

The refined sound caught the ear of XL records founder Richard Russell, who quickly championed Umoh’s talent, enlisting him for his Everything Is Recorded project. The collaboration instantly elevated Umoh, throwing him into a new world, placing him alongside fellow contributors to the project including Kamasi Washington and Sampha.

“I was used to going on Soundcloud and searching for beats and it threw me into this world where everything was so raw and real and true,” says Umoh. “I remember having this conversation with Richard about this quarrel with myself, that I’m trying to come into my own voice and he said to me: ‘You’re in a very unique position because you can do both—you’re not in Nigeria any more, so you can pull influences from Nigeria and from Britain and merge it together to create this beautiful thing’. I was working on my EP Home at the time and if you listen to the project it’s like a mix of two different things—almost like an argument between the old and the new, trying to understand what I really was.”

Coming into himself as a musician, Umoh began to understand that he needed to go back to his roots. This realisation and the sounds it resulted in, necessitated a new name that would properly reflected Umoh’s new found clarity and confidence. “That got me thinking about a name and what i should call myself,” Umoh begins. “My Dad’s name is Steven, so my family call me Junior. ‘Obong’ in my language means king or God essentially, so I put Obong in front of the Jr and ‘Obongjayar’ came out. To me it means power.”

Although Umoh says he’s not a religious person, there’s clearly a spiritual aspect to his work. Umoh speaks of Friends of Jesus, the church his grandmother would take him to as a child, with high regard, saying that it’s focus was less on bible preaching but on community and life lessons. When they’d speak about heaven and hell they weren’t literal places with burning flames, but often metaphorical—hell as a place of your own making in this world.

“We had no instruments in the church, we’d just sing acapella and clap our hands. You go to certain churches and it’s very bible orientated, but this was more of a family situation, it was community and we talked about real life situations and how to live. I’m a vegan now but my earliest memory of eating a plant based diet was from the church and this was in the 90s—the preacher called it ‘electric foods’, having foods from the earth to get your body charged and this was in conversations we were having in church. It was fucking great.”

Umoh speaks of the value of some religious teachings but can not reconcile their archaic take on things—including the “bare homophobia”—or the “bloodbath” behind Christianity’s origins in his native Nigeria.

Is there irony in his move from Nigeria to the United Kingdom with its legacy of colonialism?

“It’s life, you’ve got to go where the opportunity is, this is where the opportunities are and I’m here. It’s a different time. It’s like coming from nothing, you’re not going to glorify nothing, you’re going to glorify the come-up and how you’ve been able to transcend from that by speaking about your past situation.”

Umoh speaks about personal responsibility and the limitations of being able to singularly change the world. He talks about making peace with the idea that there are things that are beyond our control and the freedom that grants you to focus on doing your own thing as a means to express your point of view and influence others: “That’s all you can do as a human being—pass on information to the people who are around you so that you influence them in however you see fit. But don’t forget as you are doing that some else who is a racist is doing that too—it’s a weird web.”

“There’s no use trying to force people to see things from your point of view—you can only change your immediate environment. Trying to change the world is bullshit bro. Martin Luther King fought for the freedoms of black people and to an extent he succeeded, but the same oppressions are still going on today. You can try to have discourse and change people’s minds but there’s no guarantee. There are people that think the world is flat! The revolution isn’t going to happen at once, it takes time and it trickles down.”

Words—their meaning, their motivation, their sound—are essential ingredients to the Obongjayar magic. It’s something that’s evident in the way Umoh speaks, peppering his sentences with “Word, word, word” in ecstatic affirmation. Umoh speaks of his love for the “everyday man’s poet” Charles Bukowski, declaring: “You can read it, it’s profound but it’s profound in English, not in some ‘thou art this’ language. Words are important to me.”

“You can take my work and wipe your arse with it or you can take it and worship it, that’s up to you boy—if it speaks to you, it speaks to you, if it doesn’t speak to you, it doesn’t speak to you—I’ve done the work. I don’t like to explain my work because it can mean anything to anyone and who am I to tell you what you should be feeling?”