- Words Colin Gannon

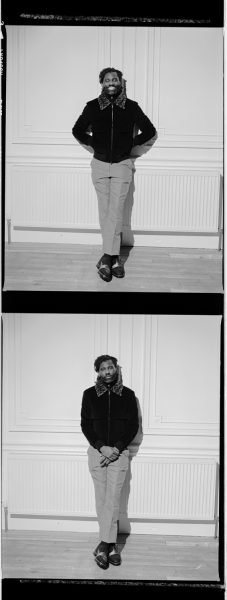

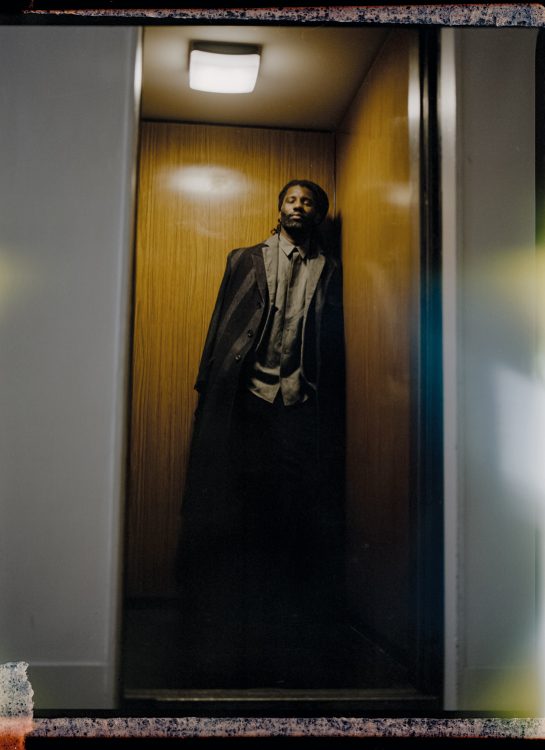

- Photography Beni Masiala

- Styling Yasmine Sabri

- Grooming Sogol Razi using NARS Cosmetics

- Styling Assistant Franck Cathus

- Production Studio Notion

- Location Green Rooms Hotel

- Special Thanks To Mr Porter, Flannels & Layers London

Not many veteran UK rappers’ names are as ubiquitous as Wretch 32. We caught up with the Tottenham titan to discuss legacy and his newfound period of self-reflection for Notion 86.

The plan was anything but straightforward: Peak by the time you’re 32. Ambitious and bold by any standard. Even early on in his career, as a starry-eyed young hitmaker, Wretch 32 envisioned himself being in the “best shape” of his career by the time this personal milestone came around. A self-willed prophecy intended to align with his now-famous lucky numbers. Now 34, he remains as forward-thinking as ever.

Since helping form and later breaking out from grime collectives Combination Chain Gang and The Movement late last decade (both of which have since been disbanded), the cerebral rapper has never ingratiated himself with any one label, collective, or sound: Instead, he’s maintained an impressively inflexible focus on his own brand of flame-spitting, conscious rap music. He rarely does features, doesn’t adhere to any one particular production style, and the proud Tottenham native even refuses to allow geography to dictate his image, with his Twitter bio reading: “UK / Global rapper”. Wretch 32 is everywhere.

Upon Reflection, his fifth album, is a blend of life-spanning introspection and bright production. It’s a dispatch from the past handful or so years of his life, in which he has admittedly matured. Case in point being the track “Mummy’s Boy”, a subversion of the pejorative that was regularly lobbed at him as a teenager, doubling as a heartfelt ode to his mum. Not only is this song the album’s emotional centrepiece, it is also a new personal favourite of Wretch’s.

- Cardigan Thom Browne

- Trousers Forme D'Expression

- Trainers Prada

- Cardigan Thom Browne

- Trousers Forme D'Expression

Hindsight has allowed him to re-evaluate what his mother, who raised him and his five sisters alone, means to him, alternately describing her as a “king”, a “father figure”, and on the track itself, as “Zeus”. “It’s like wow — this is what you went through on your own,” he says. “I’m an artist with a great support system, good finance — and I find it difficult. So what the hell were you going through with five children?”

The 34-year-old, born Jermaine Scott Sinclair, has spent the last decade-plus recording, touring, and raising his kids — but he’s not close to finished yet. Not least because he’s evolving as an MC. On the new album, which was surprise-released in October, Wretch sounds more emotionally plain-spoken than ever, cutting an observant and studious veteran figure in a UK rap scene full of life. Across 12 tracks, he directly addresses his now-resolved beef with Chip, interrogates his “wonder years” atop of the charts, and advocates for quiet contemplation as a remedy to modern madness. Lyrics like, “You been my nigga from we cotting / First tooth, first coup, first college / First zoot, first move, first bondage“, indicate a newfound clarity.

This breezy profundity, Wretch says, is a direct result not of perfectionism but of experience — though maybe these are one and the same. “I’m getting better all the time. I’m finding new ways to speak, I’m finding new words, I’m trying to push forward,” he says with determination, noting his abiding belief that the “great writers find new ways to tell the same story”.

Wretch also has a penchant for rhetorical colour: Periodically during conversation, he’ll pause, momentarily, before spinning off extended metaphors like an excitable Oxbridge professor, riffing on everything from adapting to the whims of streaming (“At one point, there wasn’t a toaster — there was a grill — and we had to figure out how to make toast on the grill”), to his political disillusionment (“The people who live above the ground are going to continue to make decisions for what happens underground”). Sometimes his analogies are inscrutable to fresh ears; other times he pokes inquisitively at a profound idea in a hilariously mundane way. He’s smart, wistful, eager to learn, and extremely open-minded — a natural conversationalist whose answers betray a mind that’s always working overtime.

After all these years, a curious assumption has taken hold among rap fans and critics: that his music — when separated from his rapping prowess — has been inessential. But skating back over his discography, you’ll doubtless find hard-nosed verses (“DPMP”), genre experiments (“Tell Me”), thoughtful social commentary (“Open Conversation” and “Mark Duggan”). A preternaturally gifted lyricist who grew from the original grime milieu in the late 2000s, Wretch has no illusions of grandeur and he definitely reads, questions, and considers all your critiques. All of them. Conversations about his art are welcome in this house; at least they’re happening.

It was his solo debut proper, 2008’s Wretchrospective, that formally introduced Wretch to the wider UK rap scene. Word-of-mouth buzz spread in Tottenham following Teacher’s Training Day, his 2006 debut mixtape, that he was forced to sell and distribute himself. But it was Wretchrospective that earned him the odd below-the-headline festival slot, eventually leading to a record deal with Ministry of Sound, where he released his debut studio album.

The rest is history: the tremendous success of Black and White’s singles spurred him into a commercial space few UK rappers have ever ventured. “Traktor”, the Major Lazor sampling lead single, reached number 5 in the charts. “Don’t Go”, a pillow-soft jaunt featuring Josh Kumra, went four steps further, landing at number one. His life changed forever, and his name was already etched into the history books.

But even though his time at Ministry of Sound initially paid dividends, the sudden eruption of Top 10 hits soured the working relationship. Reels of recordings were ready for release but never saw the light of day. Frustration abounded. The record deal he signed, he insists today, was not inherently bad. It was a matter of conflicting interests: He wanted to change artistic direction slightly, while the label wanted to glom onto a tried-and-tested formula.

- Jacket Fendi

- Sweater Moncler

- Trousers The Row

- Shoes Christian Louboutin

Darkness set in. There were five long years of silence from the Tottenham native, who, like many before him, went from chart-topping superstar to just another young artist caught up a web of industry politicking. “What happened was, I stepped onto a field and I was selling rice and chicken, and everybody liked the rice and chicken,” Wretch explains, as if there is no other way of putting it. “Then I came back the next season and I now decided I wanted to make vegetarian food.”

Moving to Polydor, in 2016, gave him a new lease of life. His sophomore album, Growing Over Life, was an explicit reaction to this creatively restricting period of his life. When recalling the borderline furious mindstate that went into recording the album, his throat rumbles: “Oooooof”.

Now, he’s still making albums and still a name to look out for. Gripping onto relevancy is no mean feat. Aging can soften ruthless streaks, change motivations, breed cynicism, but Wretch’s best impulses remain intact. “I still write and record because I need to — for me. I think I’ve found a great way of expressing myself.”

It can sometimes be hard to say whether he has fulfilled his early promise, or hovered below (arguably unfair) expectations. Some people cherish his pop hits, while others rhapsodise his blistering, canonised freestyles. Wretch grew from grime, but never felt pressured to stick to rhyming over grime riddims. Which is not to say that Wretch was ever a dedicated grime artist — he is a rapper, an MC, a lyricist, and now, an author. Days after we jump on the phone, Wretch’s first book, Rapthology, hit shelves. Part-autobiography, part-memoir, part-creative rap how-to manual, Wretch has entered a new realm with his debut book. But, to him, it’s just another “string on my bow”.

Otherwise calmly articulate and personable, Wretch’s voice raises a register when speaking about legacy and perceptions of his art. He’s just at that point in his life, he says, where every decision, mistake, and moment worthy of remembering are being mulled over. Thankfully, he doesn’t expound some inane one-fits-all ethos for self-reflection, and he doesn’t let allow himself—or the resulting music—to become too solipsistic or unfair on a past self. This honesty has not spilled over into him getting therapy or watching mindfulness techniques on YouTube; he continues to find solace in music and family.

There’s nothing enormously pain-stricken on the new record. Nor is there any socially conscious deep cuts. It’s an album by Wretch, for Wretch. Just like always.

- Shirt & Blazer Forme D'Expression

- Coat Yohji Yamamoto

- Trousers Barena

- Loafers G.H. Bass

What feeds into your creativity with words? Do you read voraciously or is it something that comes naturally to you?

It’s just my writing process, man. I literally just figure things out. For example: I’ll think of what my mum means to me, and how I feel about her today. Okay cool; so how can I speak about this in a way that I haven’t before? Let me figure out a concept that I haven’t used: mummy’s boy. That was something I was mocked for, but then it’s like: Let’s make a tune where I’m biggin’ up my mum. But at the same time, I’m taking a connotation that was once negative and I’m turning it into a positive because the kid who was the mummy’s boy is now the man of the house. So it’s about how you can continuously add layers to a narrative, and then still keep it entertaining and still hit the bullet points. That’s the process I enjoy.

A lot of your songs ooze empathy. To what extent do you think art can make people more empathetic? Is there any album or song or movie that you can point to that changed your mind about a specific subject, and do you hope your art does something similar?

Defo. I’m a massive Jay-Z fan, and he’s a senior, a role model. For argument’s sake, let’s say I thought marriage was bullshit. And now Jay-Z’s talking about how he felt marrying his woman, about how it feels to tell his child about their mother, which is his wife. Now, as a human, I empathise with it and I’m like: that feeling must be incredible. I now understand [marriage] in a different way than I did before. That’s what sensible artists are supposed to be doing. You might think something is corny, but we’re supposed to be changing [people’s minds] on things.

Musically, the new album is quite diverse, and the contrast between heavy and light subject matter and sound is most obvious when it goes from “Upon Reflection” straight into the more freewheeling “Spin Around”. Did you have a lot of fun making this album or was it one of the more challenging ones to make?

Making the album was the most fun I’ve ever had in my life. Cos’ you’re finding better versions of yourself. On Monday, I’m digging deep recording “Upon Reflection”, then on Tuesday, I’m recording “Spin Around”. Both are the same person — but I’m just on different wavelengths. “Spin Around” is me getting ready for a night out; “Upon Reflection” is me having a deep conversation with somebody close to me.

One thing I encountered when researching for this was a Vice article that was written a few years ago, which you ended up replying to via a further interview. I’m not sure if you remember that?

Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Where the writer was essentially arguing that, despite your clear lyrical talents, sometimes the music doesn’t live up to the performance and writing standards. Why do you think some people have that impression with your music?

Because everybody else has an idea of what you should be doing, but ultimately it’s up to me. There are some people who love when I do “Don’t Go” — I love when I do “Don’t Go” — but there are some people who prefer when I do a “Fire in the Booth” [freestyle]. If you can’t love me for both, then that’s fine. But it’s not going to stop me from doing one. You may only like your missus when she wears a dress; that doesn’t mean she shouldn’t wear trousers if she feels comfortable in trousers. That’s on you if you don’t like trousers — you get what I mean? As an artist, that’s how brave you have to be. The listener can’t dictate to you what you should be doing.

You also go on to say that, if you’re writing a song like “Don’t Go”, you want it to compete with the biggest Coldplay records. Not many artists are able to balance that kind of commercial sensibility with musical credibility. Where do you think you got this attitude from?

It’s the competitiveness, man. When I was making “Six Words”, I would only listen to Phil Collins; I would only listen to Coldplay; I would only listen to Take That. I only listened to certain artists that I feel are exceptional with simplistic melodies and really get the point. Kings of Leon even. I put myself in that realm and it enables me to almost create at that level. Just like when I’m going to do a “Fire in the Booth”, I think about the people who have the best ones — Ghetts, Stormzy, and Avelino — and I think: ‘How can I compete? Where’s my point-of-difference?’ I work it out, and I strike. It’s being competitive in every field, man. I can play in the Premiership, I can play in the World Cup — and I can play in the Champions League. You know those players who are great in the Premiership but disappear in the World Cup?

Yeah. Wayne Rooney or someone.

That’s not me.

- Cardigan Thom Browne

- Trousers Forme D'Expression

- Trainers Prada

One thing that you often end up reverting back to when discussing your music is legacy—the importance of that to you right from the day you started up until today. Do you get frustrated when people say you’re underrated or is that some kind of indicator that you’re doing something right?

It’s a thin line because once people put those kind of words into the atmosphere, it makes people look at you a certain way. But I do understand why people feel like that, because people are like: ‘No man, you should be like J Cole and Kendrick Lamar’. I get why they feel like that, but at the same time, it does put something in the air that doesn’t need to be there.

What drives people to believe this? Are these expectations unfair?

They wanna see me on top of the world! They wanna see me rap alongside Kendrick Lamar, Jay-Z, J Cole. They wanna see me going head-to-head with the people who rap how I rap. I understand their frustrations because I wanna see myself there as well but I understand everybody has got a route, ya know. Some things are for you today, and some things are for you tomorrow.

And are you happy with how your career has taken shape, musically?

I’m happy because I’m important. I’ve been rapping for longer than I haven’t been rapping. I’m 34. I’ve been in the industry for 10 years and I’m still significant. I’ve seen people who haven’t lasted 10 months. We’re still here, we’re still doing interviews with yourself, we’ve even got a new book coming out, and that’s a new plateau for me. I’ve raised the bar for myself. Let’s step into new territory and let’s add value in that department as well. Let’s see how far we can push our legacy — and that’s where I’m at this moment in time.

You’ve described your early successes as a blessing and a curse. What does success look like to you today?

I’m just a small part to play in a bigger picture. I can’t feel successful until everyone is on the same stage.